-

The atomic nucleus is a quantum many-body system composed of protons and neutrons, whose properties are determined by the strong interaction between nucleons [1]. The nuclear force is non-central, non-local, and energy-dependent, and it remains not fully understood at present [2]. The study of mirror nuclei provides an important means to test the charge independence and isospin symmetry of the nuclear force. For example, the mass relationships of mirror nuclei are closely related to isospin symmetry in nucleon interactions [3−6]. Since nuclear theory generally treats protons and neutrons as identical particles, they usually possess the same properties, including ground-state parity and angular momentum [7]. Near the β-stability line, the breaking of mirror symmetry in the nuclear force of bound nuclei is often negligible. However, in nuclei far from the β-stability line, especially near the proton drip line, the symmetry of the nuclear force may be broken due to the influence of the Coulomb force, changes in nucleon-nucleon interactions, and shell effects [7−9].

Recently, with the rapid development of radioactive ion beam (RIB) technology, experiments have achieved the synthesis and study of nuclei near the proton drip line. To date, several major experimental facilities related to this field are in operation, undergoing upgrades, under construction, or have been proposed both domestically and internationally. These include the Radioactive Ion Beam Line (RIBLL) at the Institute of Modern Physics in China, the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB) at Michigan State University in the United States, the Radioactive Isotope Beam Factory (RIBF) at the RIKEN Institute in Japan, and the Facility for Antiproton and Ion Research (FAIR) at the Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research in Germany, and so on. Nuclei near the drip lines typically exhibit extreme proton-to-neutron ratios and display unique structural and dynamical properties, such as shell evolution [10] and proton halo structures [11], making them a frontier area of nuclear physics research [12]. The investigation of collective properties, such as vibrations and rotations, and symmetry-breaking phenomena in mirror nuclei near the proton drip line not only deepens our fundamental understanding of nuclear forces but also provides critical insights into nucleosynthesis processes in nuclear astrophysics [13, 14].

To date, 50 pairs of even-even mirror nuclei have been synthesized experimentally [15]. These nuclei range from Z = 2 (He) to Z = 48 (Cd) and are concentrated near the proton drip line. Nuclei close to the proton drip line exhibit numerous novel phenomena—for example, 8B [16] and 17Ne [17] are typical proton halo nuclei. Theoretically, Ref. [18] predicted two-proton halo nuclei with A = 18-34 using the relativistic mean field plus BCS method. However, in heavier nuclear regions, further theoretical and experimental efforts are still needed to predict and verify proton halo nuclei. Ref. [19] indicated that the ground states of the mirror nuclei 70Kr and 70Se may have different shapes; Ref. [7] reported evidence of distinct ground-state spins for 73Sr and 73Br; Ref. [20] proposed that electromagnetic and isospin-breaking effects lead to the neutron-proton mass difference. All these studies demonstrate the existence of charge symmetry breaking in atomic nuclei. In this paper, we selected three pairs of mirror nuclei (74Kr-74Sr, 78Sr-78Zr, and 82Zr-82Mo) for research. The selected mirror nuclei are located in the A≈80 region, which is known for rapid shape transitions, large deformations, and strong evidence of shape coexistence [21−23]. These nuclei lie near the proton drip line and exhibit extreme proton-neutron ratios, making them ideal for studying isospin symmetry breaking under the influence of the Coulomb force and shell effects. Additionally, these pairs are accessible with current radioactive beam facilities and have sufficient experimental data for comparison. The violation of symmetry in excited-state energy levels poses significant challenges for current theoretical studies. How to accurately interpret and describe these complex physical phenomena remains a key unresolved issue urgently requiring attention in nuclear physics.

A suitable tool for investigating the rotational properties of mirror nuclei is the total Routhian surface (TRS) approach, which usually describes the bulk properties of medium and heavy nuclei well and has the advantage of simplicity of physical picture and calculation. Previously, we systematically studied various isotopic and isotonic chains, such as 132-138Nd [24] and 118-128Ba [25] isotopes,

$ N=76 $ [26] and$ N=104 $ [27] isotones, employing the pairing self-consistent Woods-Saxon potential within the TRS framework, focusing on nuclear shape evolution, rotational behavior, and shape coexistence phenomena. The TRS calculations successfully reproduced experimental observables such as the adopted$ \beta_2 $ deformations (deduced from B(E2) values) [28], moments of inertia (MOIs), and band-crossing phenomena like backbending and upbending [29, 30]. The interplay between proton and neutron alignments, especially in high-j orbitals near the Fermi surface, was shown to influence rotational properties and shape changes, including the coexistence of prolate, oblate, and superdeformed configurations. Overall, the TRS method proves to be a robust and insightful framework for understanding the complex rotational and structural behaviors of mirror and midshell nuclei.This article is structured as follows. In Section 2, we provide a detailed specification of the current TRS calculations within the framework of the Microscopic-Macroscopic (MM) model. Section 3 presents the results obtained for the ground state and rotational properties of the mirror nuclei, accompanied by a thorough discussion and interpretation of these findings in the context of existing literature. Finally, Section 4 summarizes the main conclusions drawn from this work and offers perspectives for future research.

-

In the present work, the multidimensional TRS calculation is based on theoretical framework associated with the MM model and the cranking shell model [31, 32]. This method is highly effective in the study of high-spin phenomena in medium and heavy-mass nuclei. The total Routhian is the sum of the energy of the non-rotating state and the contribution due to cranking. Its expression is as follows [24, 30, 33]:

$ \begin{aligned}[b] E^\omega(Z, N, \hat{\beta}) =& E^{\omega=0}(Z, N, \hat{\beta}) + \left[ \langle \Psi^\omega \vert \hat{H}^\omega(Z, N, \hat{\beta}) \vert \Psi^\omega \rangle \right. \\ & \left. - \langle \Psi^\omega \vert \hat{H}^\omega(Z, N, \hat{\beta}) \vert \Psi^\omega \rangle^{\omega=0} \right]. \end{aligned} $

(1) where the energy

$ E^{\omega=0}(Z,N,\hat{\beta}) $ , which consists of a macroscopic part and a fluctuating microscopic one, is the energy of a non-rotating state. The last term in the square brackets represents the contribution resulting from rotation, as included in the expression. The expression for the energy of the non-rotating state is as follows:$ E^{\omega=0}(Z,N,\hat{\beta}) = E_{{\rm{macr}}}(Z,N,\hat{\beta}) + E_{{\rm{micr}}}(Z,N,\hat{\beta}). $

(2) where the former term represents the macroscopic part, and it is derived from the sharp-surface standard liquid-drop formula that adopts the parameters put forward by Myers and Swiatecki [34]. The latter term represents the microscopic correction part; its expression is given below:

$ E_{{\rm{micr}}}(Z,N,\hat{\beta}) = \delta E_{{\rm{shell}}}(Z,N,\hat{\beta}) + \delta E_{{\rm{pair}}}(Z,N,\hat{\beta}). $

(3) The former term represents the shell correction component, computed via the Strutinsky method [35]. Here, the Strutinsky smoothing procedure adopts sixth-order Laguerre polynomials, and the smoothing range is set to

$ \gamma = 1.20 \;\hbar\omega_0 $ (with$ \hbar\omega_0 = 41/A^{1/3} $ MeV). The latter term represents the pairing correction component, computed using the Lipkin-Nogami method [36], which prevents the spurious pairing phase transition that arises in Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) calculations. The monopole and quadrupole pairings are considered. The monopole pairing strength is calculated by the average gap method [37], while the quadrupole pairing strengths are determined by restoring the Galilean invariance broken by the seniority pairing force [38]. Both shell corrections and pairing corrections are evaluated based on a set of single-particle energy levels. The single-particle energies applied here are obtained from the phenomenological Woods-Saxon (WS) potential [31, 39], whose parameter set is widely employed in cranking calculations [40]. For the diagonalization of the WS Hamiltonian, deformed harmonic oscillator states with principal quantum number$ N \leqslant 12 $ and$ N \leqslant 14 $ are adopted as the basis states for protons and neutrons, respectively.Nuclear shape is defined by a standard parameterization method, in which the nuclear shape is expanded in terms of spherical harmonic functions [39], and its expression is as follows:

$ R(\theta, \phi) = R_0 c(\hat{\beta}) \left[ 1 + \sum\limits_{\lambda=1}^{\infty} \sum\limits_{\mu=-\lambda}^{\lambda} \alpha_{\lambda\mu} Y_{\lambda\mu}^{*}(\theta, \phi) \right]. $

(4) where it is particularly suited for analyzing symmetry characteristics [41]. In the present work, the deformation parameters

$ \hat{\beta} $ include the axial quadrupole deformation$ \beta_2 $ , the nonaxially quadrupole deformation (triaxial) γ, and the hexadecapole deformation$ \beta_4 $ .Cranking restricts the nuclear system to rotate about a fixed axis (e.g., the x-axis) at a specified rotational frequency. Pairing correlations depend not only on the rotational frequency but also on nuclear deformation [25]. The cranked-Lipkin-Nogami equation obtained in this way has the form of the well-known Hartree-Fock-Bogolyubov (HFB) equation [32]. For a given rotational frequency and deformed lattice points, the pairing problem can be self-consistently handled by solving this equation with a sufficiently large WS single-particle state space. Certainly, the symmetry of the rotational potential can be used to simplify the cranking equation. In the case of reflection symmetry, intrinsic parity π and signature r are both good quantum numbers. Solutions featuring

$ (\pi, r) $ provide energy eigenvalues at the same time, and from these, the energy relative to the non-rotating state can be derived directly. After the Routhian is calculated at a fixed rotational frequency ω, it is interpolated between lattice points using a cubic spline function, and the equilibrium deformation can be determined by minimizing the computed TRS. In addition, the HFB method also allows for the approximate calculation of the total angular momentum as a function of the rotational frequency ω, from which several quantities such as the kinematic and dynamic MOIs, and the aligned angular momentum with proton and neutron components can be derived. The total collective angular momentum is calculated as follows [30, 42]:$ I_x = \sum\limits_{\alpha,\beta>0} \langle \beta | j_x | \alpha \rangle \rho_{\alpha\beta} + \sum\limits_{\alpha,\beta>0} \langle \bar{\beta} | j_x | \bar{\alpha} \rangle \rho_{\alpha\bar{\beta}}. $

(5) where ρ is the density matrix in the signature basis, where

$ \alpha, \beta $ label the basis states and$ \bar{\alpha}, \bar{\beta} $ correspond to states with opposite signatures. The MOIs are derived from the formula$ J^{(1)}=I/\omega $ .In the actual calculation, the Cartesian quadrupole coordinates

$ X=\beta_2 $ cos$ (\gamma+30^\circ) $ and$ Y=\beta_2 $ sin$ (\gamma+30^\circ) $ , consistent with both the Bohr shape deformation parameters and the Lund convention [43], are employed. The deformation parameter$ \beta_2 $ is constrained to positive values, while γ spans from$ -120^\circ $ to 60°, covering three equivalent sectors representing identical triaxial ground-state shapes. Three sectors [$ -120^\circ $ ,$ -60^\circ $ ], [$ -60^\circ $ ,0°], [0°,60°] represent the rotation with the long, medium, and short axes at a given rotational frequency. At each (X, Y) point on the deformation grid, the nucleus’s total energy is computed following the above methodology. The potential energy surface is then constructed through cubic spline interpolation across these lattice points, enabling detailed extraction and analysis of nuclear characteristics such as ground-state equilibrium deformations, binding energies, and angular momentums. -

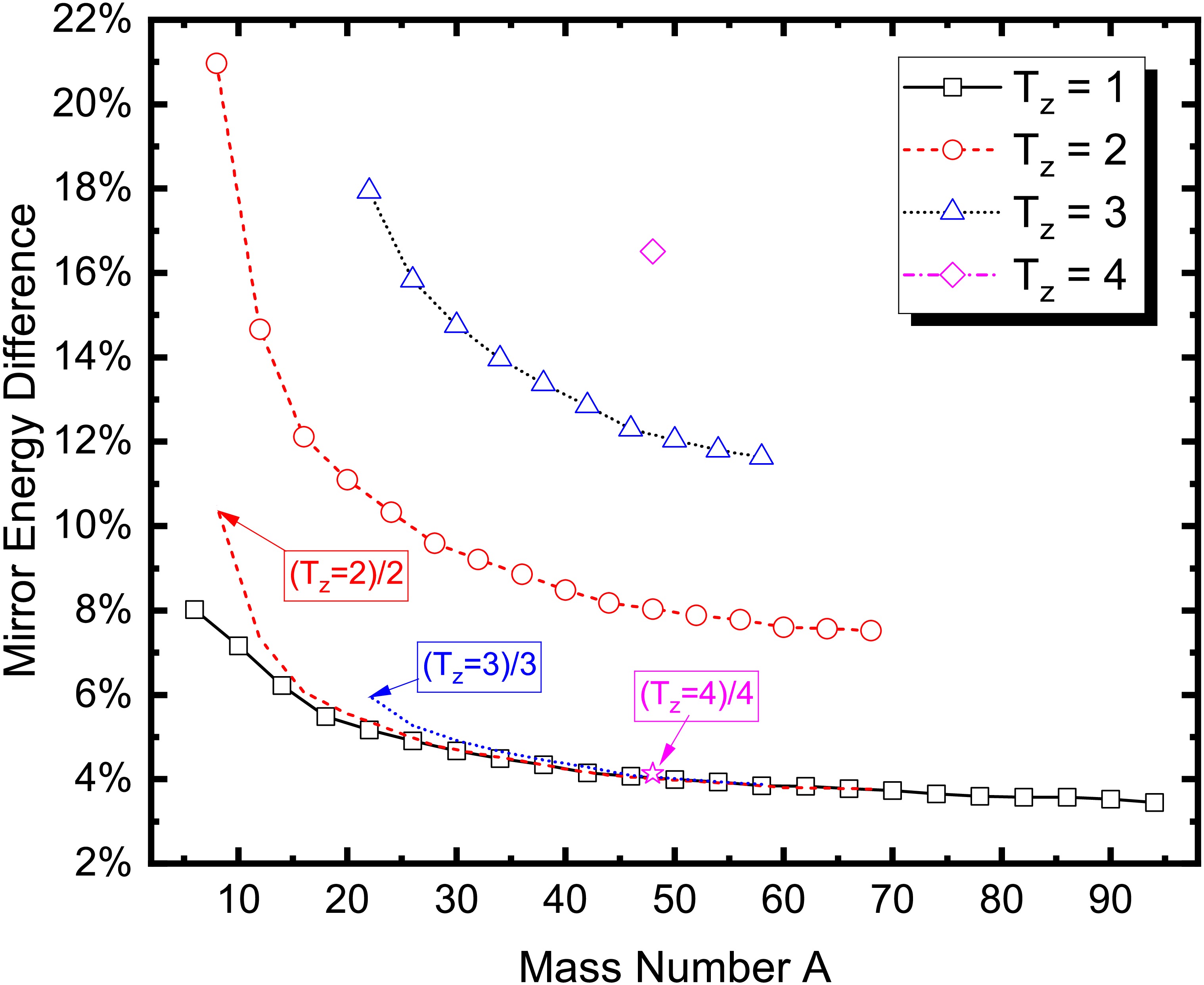

The study of mirror nuclei in nuclear physics offers valuable insights into the fundamental properties of atomic nuclei, particularly regarding the mass differences between such pairs. Mirror nuclei are pairs of isotopes where the number of protons in one nucleus equals the number of neutrons in the other, and vice versa. Understanding the mass difference between these mirror nuclei is crucial for exploring the symmetries and underlying interactions within the nucleus. Amazingly, the mass formula could achieve a root-mean-square deviation of 70 keV when compared to experimental data from AME2020 [44] by utilizing the mass relation of the mirror nuclei [4]. In the present work,

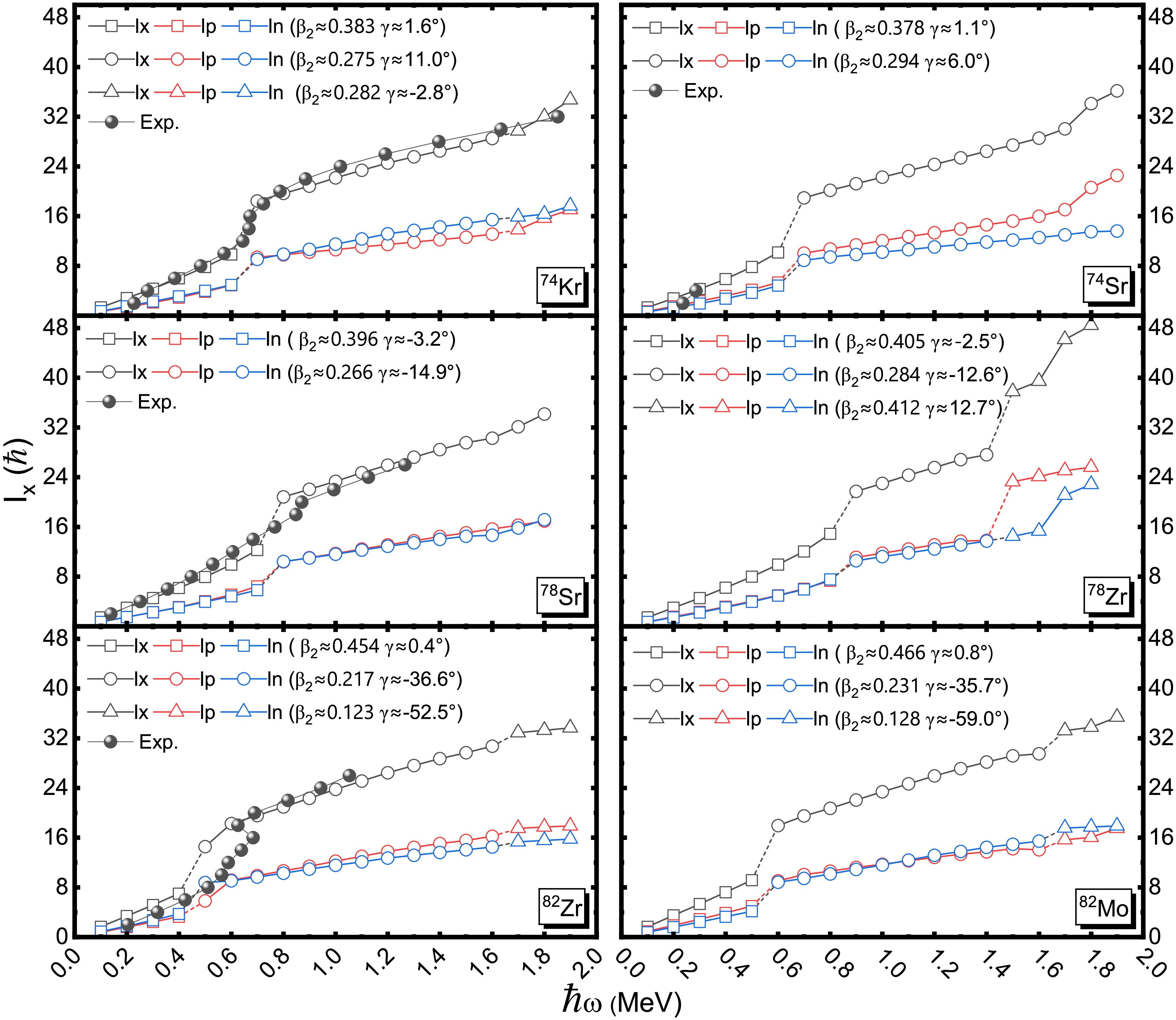

$ T_z $ represents the third component of isospin ($ \ T_z = \dfrac{N - Z}{2} $ , where the$ T_z $ of the proton is$ -1/2 $ , and that of the neutron is$ 1/2 $ [1]). Figure 1 shows the experiment mirror energy difference (MED) in the available 50 even-even nuclei [44], including four categories labelled$ T_z=1 $ ,$ T_z=2 $ ,$ T_z=3 $ , and$ T_z=4 $ . Indeed, the MED with ($ T_z $ =2)/2, ($ T_z $ =3)/3, and ($ T_z $ =4)/4 will nearly coincide with that of$ T_z=1 $ . As the mass number of mirror nuclei increases, the MED between the pairs tends to approach a constant value of approximately 3.6%. This finding is significant as it indicates a structural pattern closely linked to the intrinsic properties of protons and neutrons, rather than being a random or isolated phenomenon. Remarkably, this 3.6% difference closely matches the mass disparity between two protons and two neutrons, suggesting that the origin of the mass discrepancy lies fundamentally in the nucleons themselves. The mass difference in mirror nuclei primarily arises from the interplay between the masses of protons and neutrons and the electromagnetic interactions within the nucleus. Moreover, the Coulomb force plays a pivotal role in contributing to the MED between mirror nuclei. The$ ab $ $ initio $ calculations has investigated of isospin-symmetry breaking in MED, primarily arising from the dominate s-wave components. [45, 46] The observed 3.6% mass difference in Fig. 1 reflects this intrinsic nucleon mass difference magnified by the nuclear environment.

Figure 1. (color online) The experiment mirror energy difference (MED) in the available 50 even-even nuclei [44]. The black squares, red circles, blue triangles, and magenta diamonds denote the MED with

$T_z$ = 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. The red dashed line, blue dotted line, and magenta star are drawn to show the MED with ($T_z$ =2)/2, ($T_z$ =3)/3, and ($T_z$ =4)/4, respectively.The mirror nuclei should have an identical set of states [47], including their ground state, even the excited state. Table 1 presents the empirical P-factor [48] and

$ R_{4/2} $ [49] experimental$ E_{2_1^+} $ [28], and the binding energies$ E_{\rm{binding}} $ for mirror nuclei 74Kr-74Sr, 78Sr-78Zr and 82Zr-82Mo. The empirical P-factor,$ R_{4/2} $ and experimental$ E_{2_1^+} $ are given to evaluate the nuclear collectivity crudely. The P-factor,$ P\equiv \dfrac{N_p N_n}{N_p + N_n} $ [54], is a sensitive indicator related to nuclear deformation. Note that$ N_p $ and$ N_n $ are the numbers of valence protons and neutrons. For these mirror nuclei, the P-factor are identical due to the same magic numbers$ Z,N=28,50 $ . Generally, the transition to deformation occurs about$ P\approx 4-5 $ . Therefore, these mirror nuclei should be deformed as the P-factors are within the above range. The energy ratio$ R_{4/2} $ equals$ E_{4_1^+} / E_{2_1^+} $ , where$ E_{2_1^+} $ and$ E_{4_1^+} $ are the first excited energy$ {2_1^+} $ and$ {4_1^+} $ . The$ R_{4/2} $ is 3.3 for a well-deformed axially symmetric rotor and 2.0 for a spherical vibrator, which are interrelated to$ SU(3) $ and$ U(5) $ dynamic symmetries by the Interacting Boson Model [49, 55, 56]. Thus, all the$ R_{4/2} $ values show undoubtedly the onset of collective characteristics. Besides, the separate$ E_{2_1^+} $ is another sensitive phenomenological quantity for studying the evolution of nuclear properties and for shell model studies [28]. The$ E_{2_1^+} $ is associated with the E2 transition probabilities or B(E2) values. For the nuclei in the$ A\approx 80 $ region, 100 keV$ < $ $ E_{2_1^+} $ $ < $ 1000 keV corresponds to$ \beta_2 \in (0.250,0.375) $ approximately. According to these empirical values, the deformed nuclear shape could be deduced in these mirror nuclei.Nuclei P-factor $R_{4/2}$ $E_{2_1^+}$ a (keV)$E_{\rm{binding}}$ (MeV)TRS FFD SHFB GHFB CDFT Exp. 74Kr 4.44 2.224 456 631.064 631.49 629.331 626.92 629.80 631.445(0.002)c 74Sr 4.44 2.214 471 608.705 608.68 607.601 604.72 607.21 608.354(0.074) Difference 0.00 0.45% 3.29% 3.54% 3.61% 3.45% 3.54% 3.59% 3.66% 78Sr 5.00 2.81 278 663.057b 663.55 661.057 659.79 662.20 663.008(0.008) 78Zr 5.00 — — 640.038 639.75 638.539 636.51 639.25 639.132(0.390) Difference 0.00 — — 3.47% 3.59% 3.41% 3.53% 3.47% 3.60% 82Zr 4.44 2.56 407 694.041 693.79 692.388 692.69 692.00 694.168(0.002) 82Mo 4.44 — — 669.786 669.06 669.212 669.21 668.26 669.366(0.410) Difference 0.00 — — 3.49% 3.56% 3.35% 3.39% 3.43% 3.57% a The uncertainties are less than 1 keV; see Ref. [28] for details.

b The bold value signifies that this value among these five theoretical ones is relatively close to experimental data.

c The bracketed numbers refer to the uncertainties deduced from Ref. [28].Table 1. The empirical P-factor [48] and

$R_{4/2}$ [49], the experimental energy of the first state$2^+$ ($E_{2_1^+}$ ) [28], and the binding energies$E_{\rm{binding}}$ for the mirror nuclei 74Kr-74Sr, 78Sr-78Zr and 82Zr-82Mo. The values of$E_{\rm{binding}}$ are given by the TRS method, and the FY+FRDM (FFD) [50], Skyrme HFB (SHFB) [51], Gogny HFB (GHFB) [52], CDFT [53] calculations, together with experiments (Exp.) [28] for comparison.In addition, the ground-state binding energy is a critical observable in nuclear physics as it reflects the overall stability and internal energy of the nucleus. The “Difference” row in Table 1 represents the percentage difference in binding energies between mirror nuclei, calculated as

$ \left| \dfrac{X(Z,N) - X(N,Z)}{X(Z,N)} \right| \times $ 100%, where X is P-factor,$ R_{4/2} $ ,$ E_{2_1^+} $ or$ E_{{\rm{binding}}} $ , respectively. From Table 1, one can notice that the precision with which our theoretical results align with experimental data and other theoretical works indicates the reliability and accuracy of the computational methods employed. The other theoretical works are obtained based on the fold-Yukawa (FY) single-particle potential plus the finite-range droplet model (FRDM), labelled FFD [50], the Skyrme HFB (SHFB) method by using the UNEDF0 force [51], the Gogny HFB (GHFB) [52] calculation, and the covariant density functional theory (CDFT) [53]. It can be seen that all the calculated values slightly underestimate the experimental data except for the microscopic-macroscopic model,$ i.e. $ , TRS and FFD results. Interestingly, our results show good agreement with experiment data in 78Sr and 82Zr. This agreement not only supports the validity of our nuclear models but also reinforces confidence in the parameters and assumptions used in the calculations.Based on the empirical values P-factor,

$ R_{4/2} $ , and$ E_{2_1^+} $ presented in Table 1, we hypothesize that the selected mirror nuclei exhibit significant nuclear deformations. To investigate this, Table 2 summarizes our calculated ground-state equilibrium quadrupole deformation$ \beta_2 $ and hexadecapole deformation$ \beta_4 $ , alongside corresponding theoretical predictions and available experimental data. The results confirm that these mirror nuclei indeed display significant deformed characteristics, reinforcing our initial speculation. In their neighbouring nuclei, the highly deformed shape has been deduced in$ N=Z $ nuclei 76Sr, 78Y, and 80Zr [57]. Focusing on the mirror pair consisting of 74Kr and 74Sr, our calculations reveal pronounced deformation values for both nuclei. Notably, the$ \beta_2 $ values we obtained for 74Kr is in closer agreement with the experimental measurement compared to other theoretical models, demonstrating the robustness and accuracy of our computational approach in capturing nuclear shape effects for this isotope. Although the calculated deformation for 78Sr is not the nearest to the experimental value, it remains well within the experimental uncertainty range, indicating that our model reliably approximates the nuclear shape in this case. In contrast, the mirror nuclei 82Zr and 82Mo present a different scenario. Our calculations identify a spherical minimum shape, corresponding to near-zero deformation, which deviates markedly from the experimentally observed deformations. Interestingly, other advanced theoretical approaches, including the SHFB, GHFB, and CDFT results, also predict spherical configurations for these nuclei. This convergence among various models suggests a persistent theoretical challenge in fully reconciling calculated and experimental nuclear shapes for this mass region. Compared with the binding energies consistent with the experimental results in Table 1, the quadrupole deformations in Table 2 seem to show a relatively large deviation from the experimental values. The binding energy is a global property that depends on the bulk nuclear matter and average interactions, which models often reproduce well. In contrast, the quadrupole deformation$ \beta_2 $ is sensitive to shell effects and the detailed balance of proton-neutron interactions near the Fermi surface. The TRS method, while accurate for energy minima, can be influenced by the choice of deformation grid and pairing treatment, leading to variations in$ \beta_2 $ . We will further analyze this discrepancy by examining the potential energy surface pictures later in the discussion. These diagrams provide detailed insights into the energy landscapes governing nuclear deformation and may help elucidate the underlying causes of the differences between theoretical predictions and experimental observations for 82Zr and 82Mo. Besides, our analysis indicates that the values$ \beta_4 $ do not significantly influence the overall nuclear deformation or the stability of the energy minima. It is important to emphasize that the TRS approach inherently favors axially symmetric and well-deformed shapes, which are energetically more favorable configurations for these nuclei [31, 32].Nuclei $\beta_2$ $\beta_4$ TRSa FFD SHFB GHFB CDFT Exp.c TRS FFD SHFB GHFB CDFT 74Kr 0.381b 0.401 0.000 −0.209 0.477 0.363(9) 0.013 0.001 — −0.006 — 74Sr 0.377 0.401 −0.106 −0.203 0.475 — 0.006 0.001 — −0.008 — 78Sr 0.396 0.403 0.366 0.00 0.492 0.413(21) −0.012 −0.020 — 0.00 — 78Zr 0.404 0.417 0.374 0.00 0.493 — −0.015 −0.041 — 0.00 — 82Zr 0.002 0.443 0.000 0.00 0.000 0.368( $^{+24}_{-10}$ )−0.001 −0.042 — 0.00 — 82Mo 0.002 0.465 0.000 0.00 0.000 — −0.001 −0.020 — 0.00 — a The calculated triaxial deformation $ |\gamma| $ are less than 3° in their ground state.

b The bold value signifies that this value among these five theoretical ones is relatively close to experimental data.

c The bracketed numbers refer to the uncertainties in the last digits of the quoted values; see Ref. [28] for details.Table 2. The calculated ground-state equilibrium quadrupole deformation

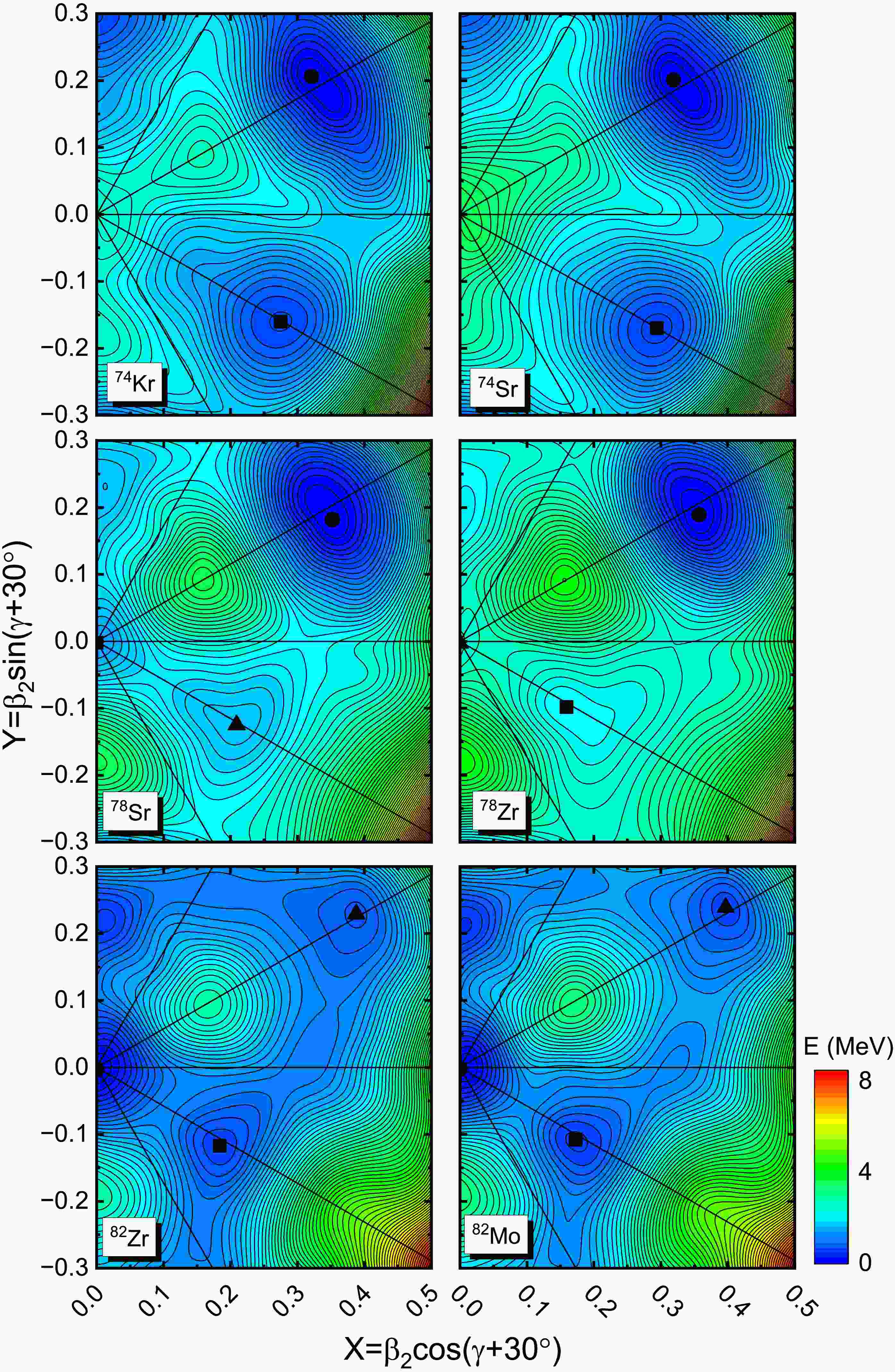

$\beta_2$ and$\beta_4$ for the mirror nuclei 74Kr-74Sr, 78Sr-78Zr and 82Zr-82Mo. The$\beta_2$ and$\beta_4$ values are given by the TRS method, the FFD [50], SHFB [51], GHFB [52], and CDFT [53] calculations, together with partial experiments (Exp.) [28] for comparison.Figure 2 presents the potential energy surfaces (PES) for the mirror nuclei 74Kr-74Sr, 78Sr-78Zr and 82Zr-82Mo at ground state. All these pairs exhibit the phenomenon of shape coexistence, where multiple distinct nuclear shapes appear as local minima in the energy landscape. This coexistence highlights the complex structural behavior of these nuclei and the delicate balance of nuclear forces that stabilize different configurations. For the pairs 74Kr and 74Sr, as well as 78Sr and 78Zr, the ground states correspond to prolate shapes. Both 74Kr and 74Sr also show a secondary oblate minimum, indicating the presence of competing shapes close in energy. The prolate-oblate shape-coexistence in 74Kr has been confirmed using combined conversion-electron and γ-ray spectroscopy [58]. A constrained relativistic mean field plus BCS calculation using the PC-PK1 force has also shown the shape coexistence at the ground state of 74Kr [59]. In the case of 78Sr, the second minimum is spherical, while the third minimum corresponds to an oblate shape. Conversely, for 78Zr, the second minimum is oblate and the third is spherical. This illustrates subtle differences in the shape coexistence patterns within mirror nuclei, suggesting a slight mirror symmetry violation. Notably, although the ground states of 82Zr and 82Mo are spherical, their third minima correspond to prolate shapes. The prolate deformation observed for 82Zr (

$ \beta_2=0.440 $ ) aligns closely with the experimental deformation values reported in Table 2, suggesting that the theoretical calculations capture important aspects of the nuclear shape in this mass region. The presence of shape coexistence in these mirror nuclei already hints a certain degree of mirror symmetry breaking in their ground-state configurations. This breaking of mirror symmetry reflects the complex interplay of nuclear forces and structural effects that differentiate protons and neutrons in the nucleus. Building on these findings, the next stage of investigation will focus on the rotational properties of these mirror nuclei. Studying their rotational behavior will provide further insight into the dynamics associated with shape coexistence and the degree to which mirror symmetry is preserved or broken in excited states. This continued research will deepen our understanding of nuclear structure in mirror systems.

Figure 2. (color online) The calculated ground-state potential energy surface (PES) for the mirror nuclei 74Kr-74Sr, 78Sr-78Zr and 82Zr-82Mo. The PES has been minimized with

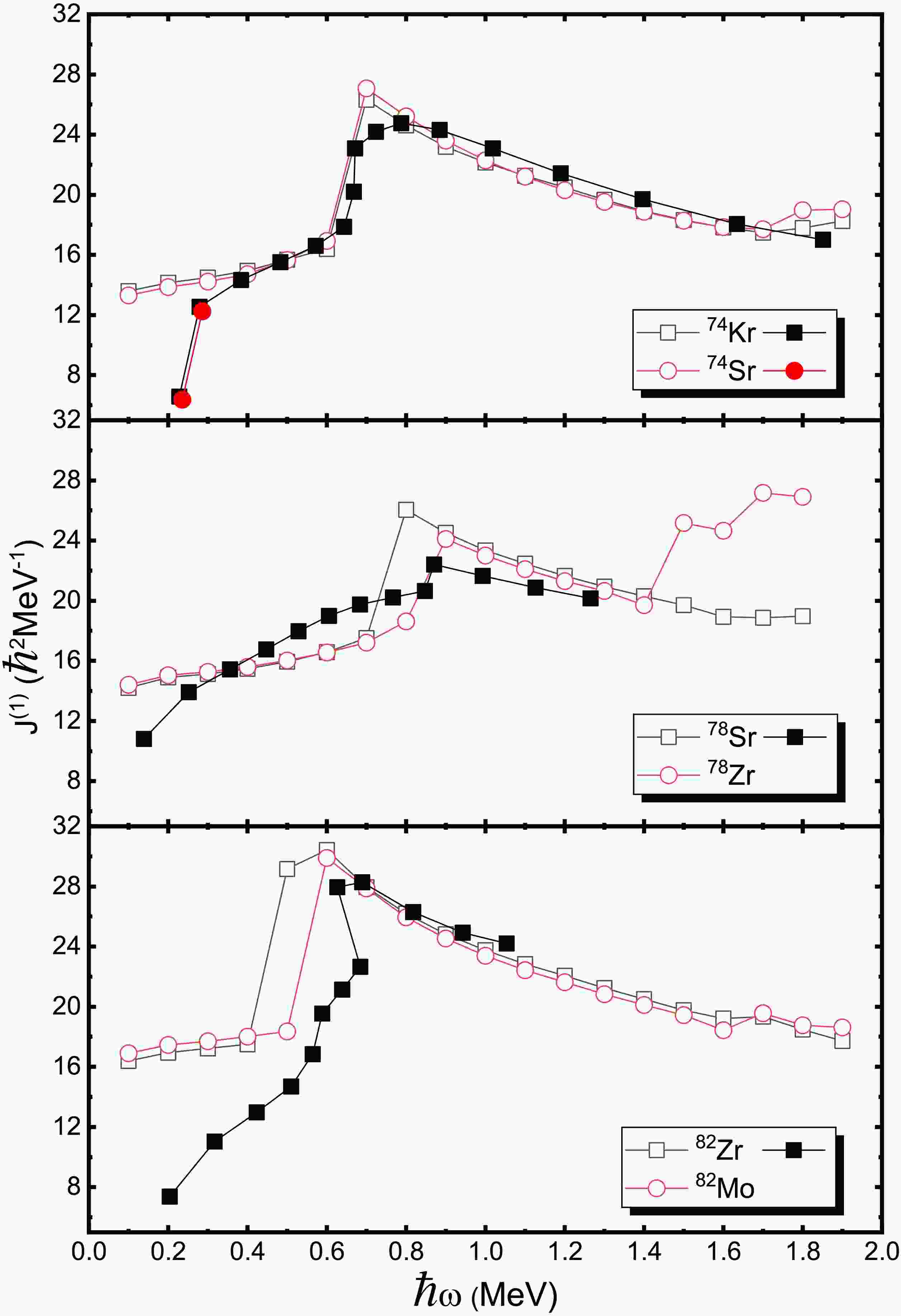

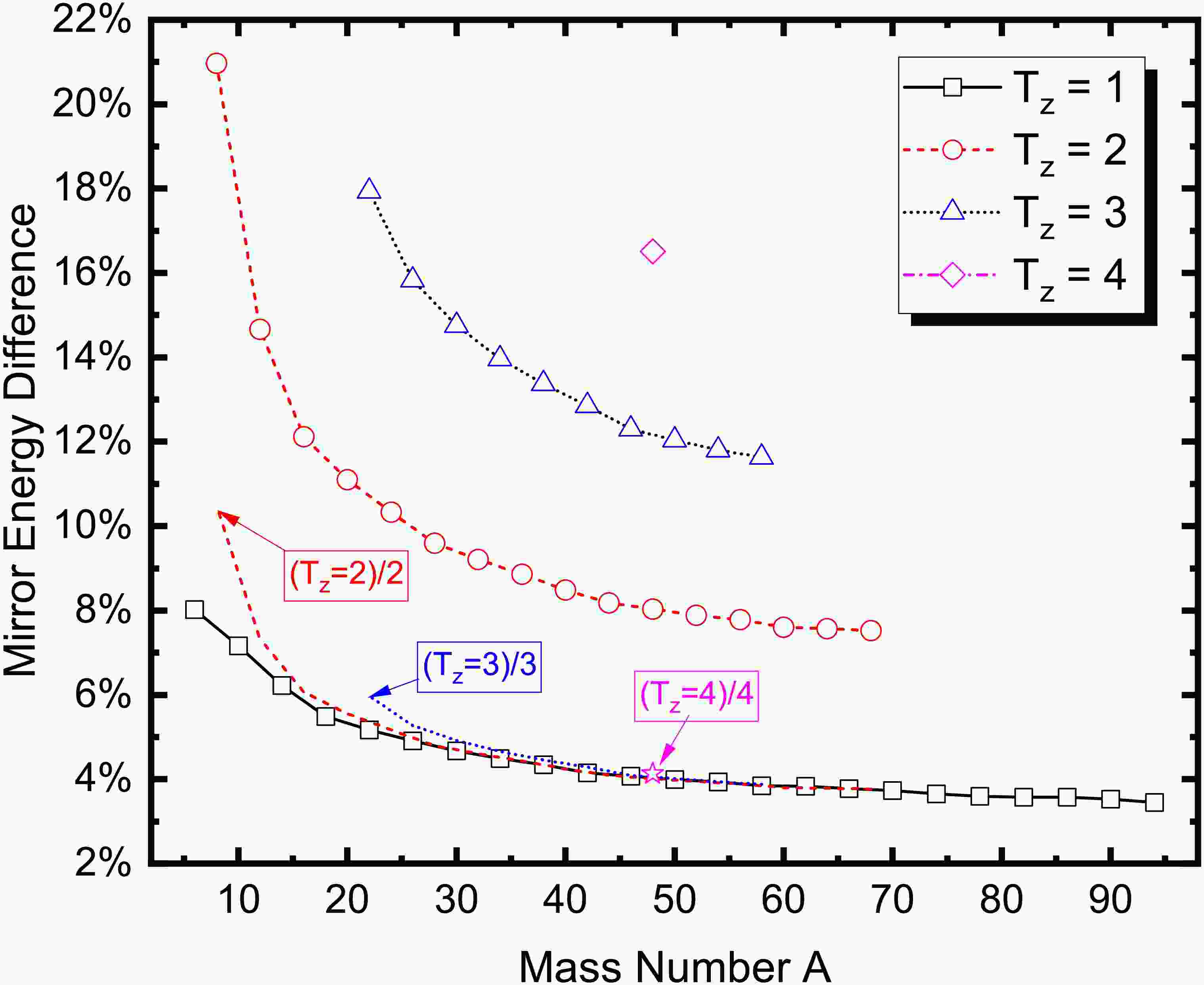

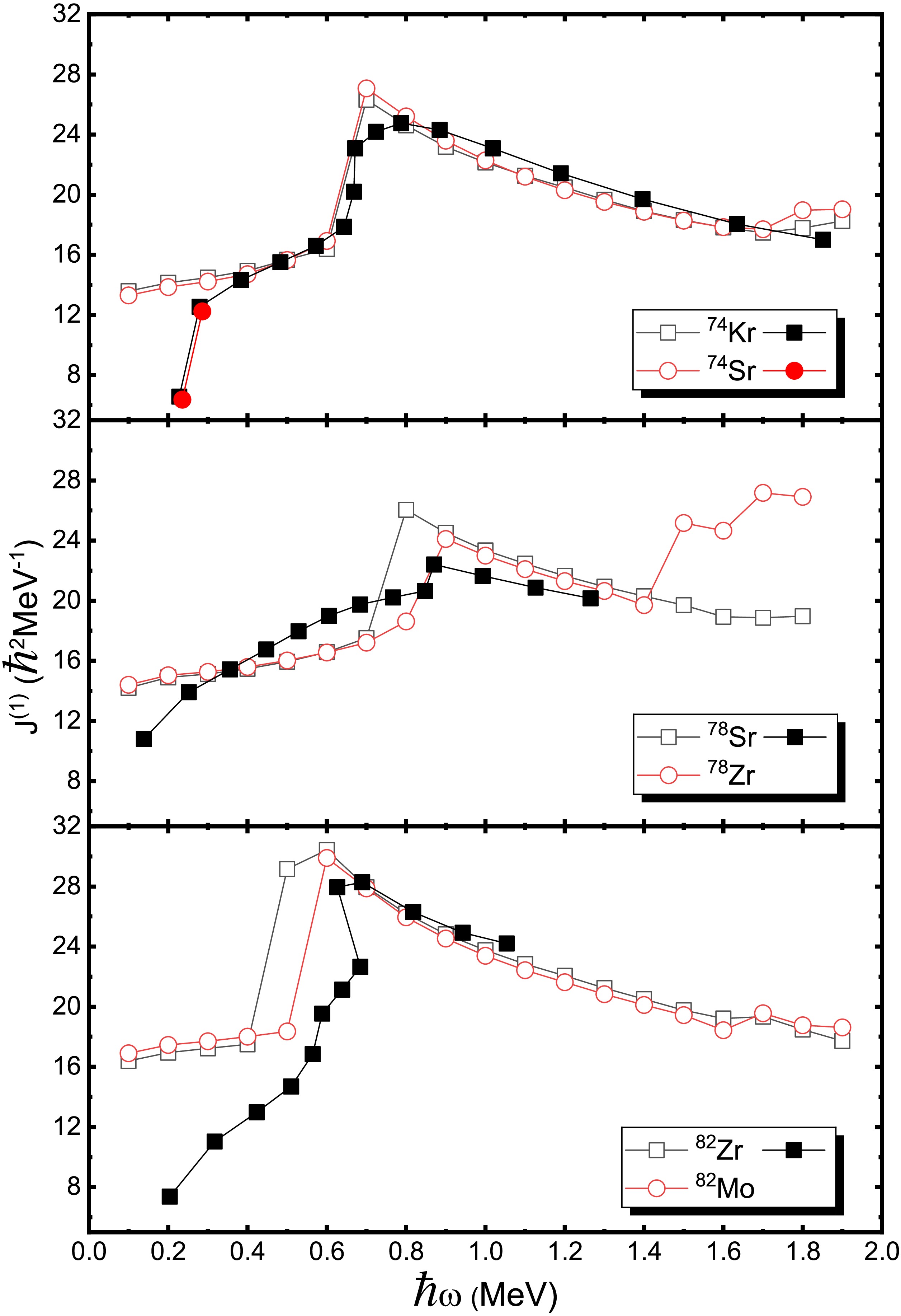

$\beta_4$ deformation at each given ($\beta_2,\gamma$ ) point. The neighboring energy contours is 200 keV. The solid circle, square and triangle represent the first, second, and third minima, respectively. Note that the first minima has been shifted to zero.Figure 3 illustrates the evolution of the MOIs as functions of rotational frequency for three pairs of mirror nuclei: 74Kr-74Sr, 78Sr-78Zr and 82Zr-82Mo. Though the experimental data are lacking for these mirror nuclei, the mirror symmetry could also be discussed to some extent based on the present computational results. Generally, our calculations successfully reproduce the experimentally observed upbending phenomenon in the MOIs across all these nuclei. As discussed in Ref. [21], high-spin structures of 74Kr and 78Sr are dominated by the shell gaps at large prolate deformation while 82Zr seems to exhibit shape coexistence for its anomaly behavior. The upbending, characterized by a sudden increase in the MOIs at certain rotational frequencies, reflects underlying changes in the nuclear structure, such as the alignment of nucleon pairs and shape transitions during rotation. In the case of 74Kr and 74Sr, the calculated changes in the MOIs show remarkable consistency between the mirror partners, demonstrating strong mirror symmetry in their rotational behavior. This agreement validates the reliability of our theoretical approach in capturing the rotational dynamics of these nuclei and highlights the symmetry between proton and neutron configurations in mirror systems at this mass region. However, deviations from perfect mirror symmetry emerge in the pairs 78Sr and 78Zr, as well as 82Zr and 82Mo. Specifically, the upbending in 78Sr and 82Zr occurs slightly earlier with increasing rotational frequency compared to their respective mirror counterparts, 78Zr and 82Mo. As can be seen from Fig. 3, the first two data points seriously deviate from the data of 74Kr and 74Sr. In the cases of 82Zr and 82Mo, our calculation results are also inconsistent with the experimental data before upward bending. This deviation may be attributed to the limitation of the adopted basis with fixed deformation, which is inadequate to characterize the near-ground-state properties dominated by shape coexistence [60]. This subtle asymmetry suggests that factors such as differences in proton and neutron interactions or shell effects may influence the rotational response differently in these nuclei, leading to observable discrepancies in their MOIs evolution. Regarding the rotational properties of 82Zr and 82Mo depicted in Fig. 3, a clarification is necessary. The calculated MOIs and deformations at rotational frequencies (e.g.,

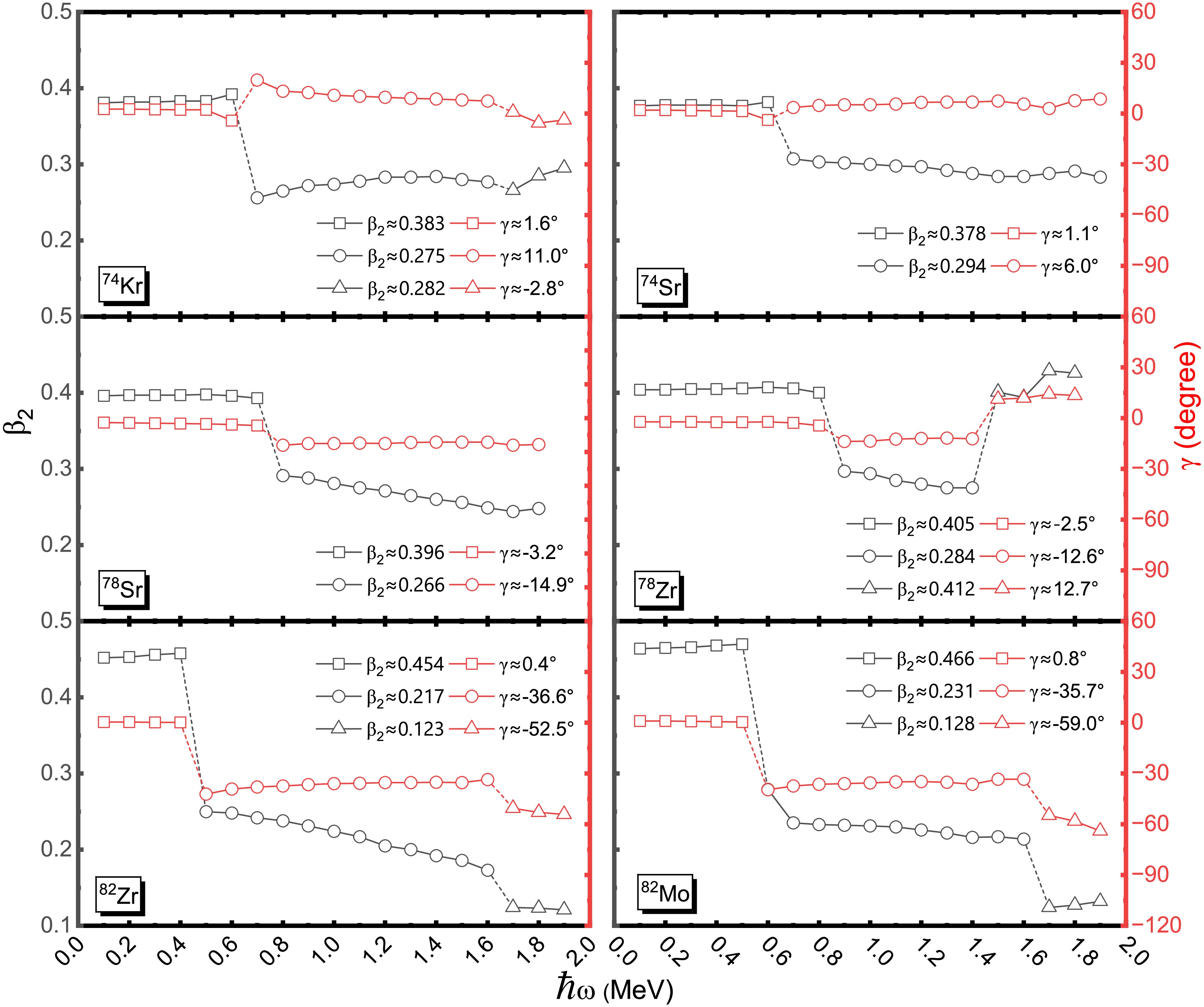

$ \hbar\omega \approx 0.1 $ MeV) do not originate from the spherical ground-state minimum identified in the static TRS calculation (Fig. 2). Instead, they correspond to the rotational band built upon the third (prolate) minimum ($ \beta_2 \approx 0.440 $ for 82Zr) in the potential energy surface. While the prolate configuration has higher energy at$ \omega=0 $ , it becomes the yrast state at higher frequencies because its larger MOI reduces the rotational energy cost. Since the angular momentum projection$ j_x $ is non-uniform across the deformation space, the TRS minimum may not always represent the actual yrast structure. This discrepancy is most pronounced at low spins, where angular momentum quantization must be strictly considered. Our analysis here focuses on the band structures that become yrast in the observed spin range.The variation in the MOIs is closely related to changes in nuclear deformation, the orientation of the rotational axis, and pairing correlations. Nuclear deformation primarily reflects the mean-field effects, which describe the average potential experienced by nucleons due to their mutual interactions. In contrast, pairing correlations arise from residual interactions between nucleons, particularly between pairs of like nucleons, and play a significant role in shaping the nuclear response to rotation. Figure 4 shows the evolution of quadrupole deformation

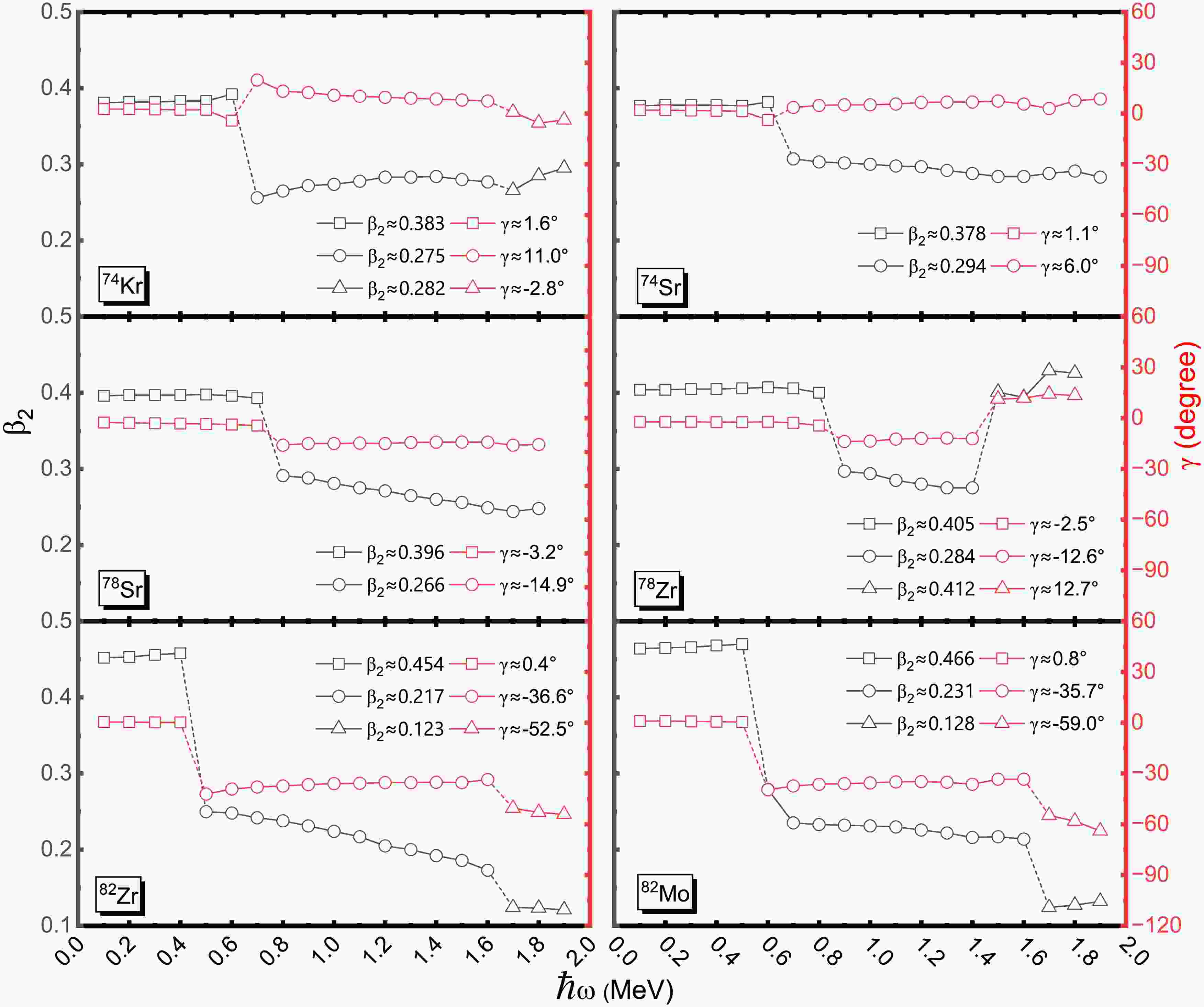

$ \beta_2 $ and triaxial deformation γ as functions of rotational frequency for the mirror nuclei studied. The mirror symmetry violation of deformation in the yrast state could also be seen in these nuclei. As the rotational frequency increases, the nuclei exhibit shifts in their dominant deformation modes, indicating changes in their shape configurations or shape fluctuations. These evolving deformation patterns correspond to variations in the nuclear potential energy landscape, influenced by the interaction between collective motion and intrinsic nucleon dynamics. Notably, at the rotational frequencies where the first upbending in the MOIs occurs, the values$ \beta_2 $ consistently decreases. This observation suggests that the increase in the MOIs-commonly associated with the alignment of a pair of nucleons—cannot be attributed to enhanced nuclear deformation. Instead, it suggests that a reduction in pairing correlations is the primary cause of the upbending phenomenon. The decrease in pairing correlations weakens the superfluid-like behavior of nucleons, allowing them to align their spins more easily along the rotational axis, thereby increasing the MOIs. This mechanism highlights the delicate interplay between collective deformation, pairing interactions, and rotational dynamics in determining the nuclear response to increasing rotational frequencies. Accordingly, the observed upbending in the MOIs of these mirror nuclei results predominantly from the attenuation of pairing correlations rather than changes in quadrupole deformation. This insight enhances our understanding of the complex interplay between mean-field effects and residual interactions in nuclear rotational behavior.

Figure 4. (color online) Calculated quadrupole deformation

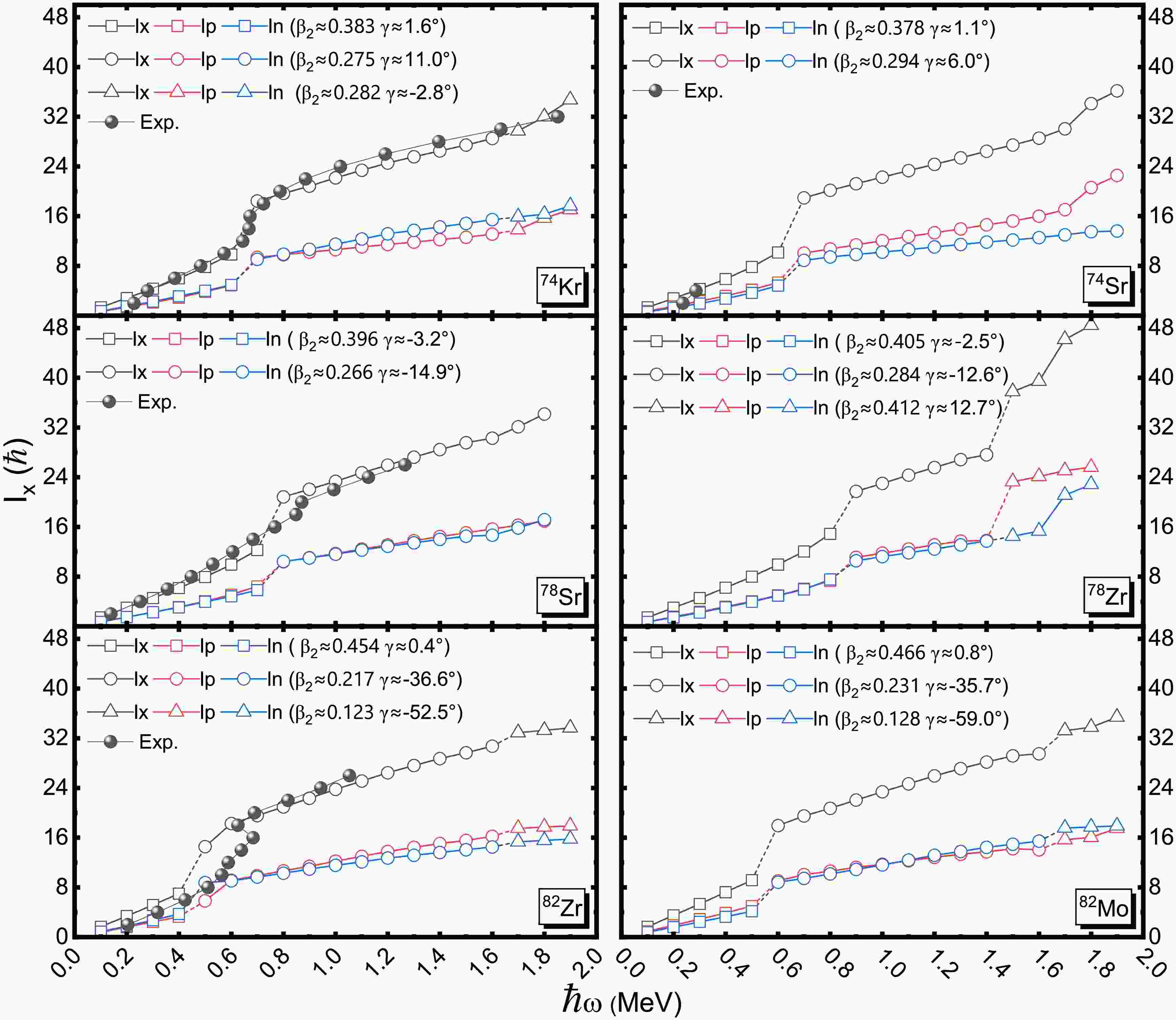

$\beta_2$ (black) and triaxial deformation γ (red) vs the rotational frequency$\hbar\omega$ for the mirror nuclei 74Kr-74Sr, 78Sr-78Zr and 82Zr-82Mo. The yrast configurations are denoted temporarily by average$\beta_2$ and γ values with different symbols.To further elucidate the underlying mechanism behind the upbending phenomenon in the MOIs, Figure 5 presents the evolution of angular momentum as a function of rotational frequency, with separate contributions from proton and neutron components to show the evolution of mirror symmetry in these mirror pairs. In the cranked Hamiltonian framework, the term involving the product of the rotational frequency and the angular momentum projection along the rotation axis (-ω

$ j_x $ ) plays a crucial role. Specifically, larger values of the angular momentum component$ j_x $ lead to more significant changes in the nuclear energy, thereby affecting the rotational response. The occurrence of upbending in the MOIs is generally associated with a reduction in pairing correlations in the present study. This weakening of pairing allows nucleons occupying high-j orbitals to break their paired configurations and align their individual angular momenta along the rotational axis, a process often referred to as band crossing or alignment. Such nucleon pair breaking and alignment result in a sudden increase in the total angular momentum, which manifests as the upbend observed in the MOIs. During the first upbending event, the increase in angular momentum arises from a nearly simultaneous and abrupt enhancement in both proton and neutron components. This coordinated behavior underscores the collective nature of the alignment process in these mirror nuclei. Indeed, delayed alignments arising from$ np $ -pairing correlation has been observed in the$ N=Z $ mirror nuclei 72Kr, 76Sr, and 80Zr [63]. However, as noted previously, the upbending in 78Sr and 82Zr occurs slightly earlier than in their mirror counterparts, 78Zr and 82Mo. This temporal discrepancy indicates that mirror symmetry is partially broken during the rotational evolution, suggesting subtle differences in the pairing and alignment dynamics between protons and neutrons within these mirror nuclei. To fully understand these asymmetries, a more detailed analysis of the individual pair-breaking processes in each mirror nucleus is required. Such an investigation would provide deeper insight into the interplay between nucleon pairing correlations, rotational motion, and mirror symmetry breaking in nuclear structure, thereby advancing our comprehension of rotational phenomena in nuclear systems.

Figure 5. (color online) Calculated angular momentum

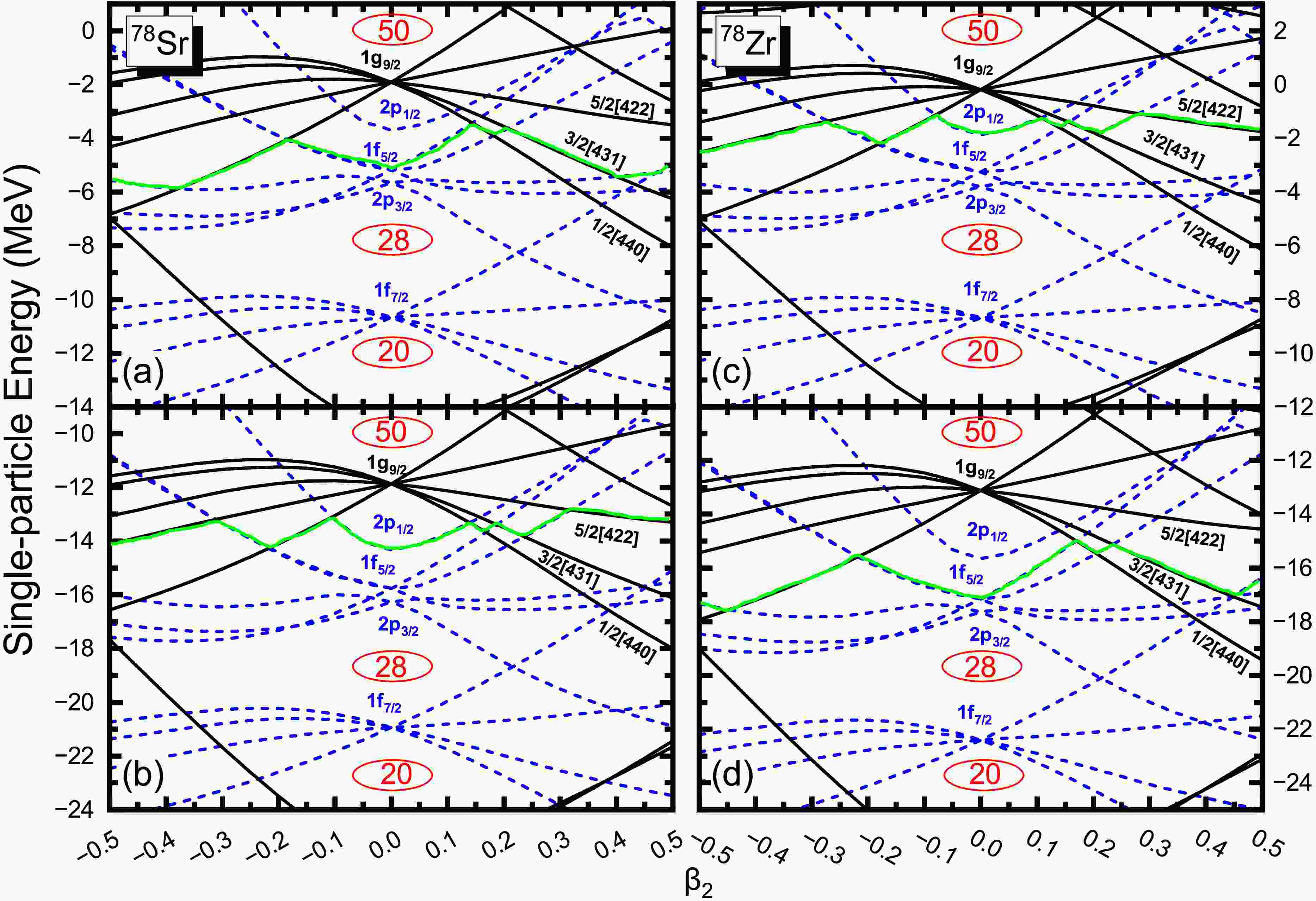

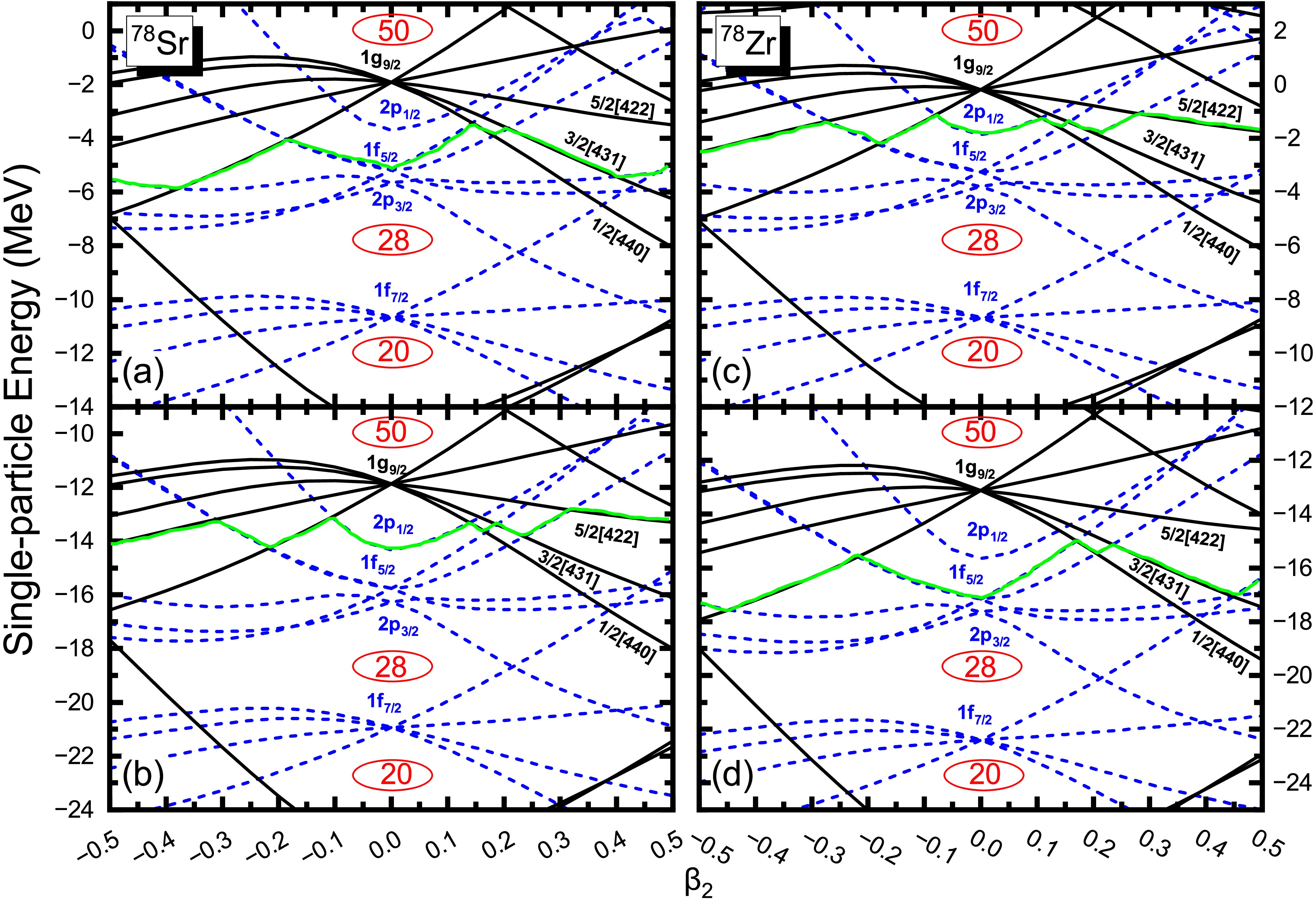

$I_x$ as a function of rotational frequency$\hbar\omega$ for the mirror nuclei 74Kr-74Sr, 78Sr-78Zr and 82Zr-82Mo. The experimental data are display with solid circles. The yrast configurations are also denoted temporarily by average$\beta_2$ and γ values with different open symbols.To identify which specific nucleon pair breaking leads to the observed alignment in the rotational behavior, Figure 6 displays the Woods-Saxon single-particle energy levels near the Fermi surface for 78Sr and 78Zr as functions of the quadrupole deformation parameter

$ \beta_2 $ . The substantial energy gaps adjacent to the Fermi level-which correspond to a low single-particle level density-are manifested as minima in the potential energy surface, as illustrated in Fig. 2 [27]. At the ground-state equilibrium deformation around$ \beta_2\approx 0.4 $ , both mirror nuclei exhibit intruder orbitals near the Fermi surface belonging to the 1$ g_{9/2} $ shell. These orbitals play a critical role in the nuclear structure and rotational properties due to their high angular momentum and proximity to the Fermi level. As the quadrupole deformation$ \beta_2 $ increases, the splitting of the single-particle levels becomes more pronounced, especially for orbitals with low projection of angular momentum on the symmetry axis (low Ω). These low-Ω orbitals shift downward in energy, making them more accessible and likely to be occupied by valence nucleons. In particular, for 78Sr, the valence protons occupy the 3/2[431] orbital, while the valence neutrons occupy the 5/2[422] orbital. In contrast, for its mirror nucleus 78Zr, the valence neutrons occupy the 3/2[431] orbital, and the valence protons occupy the 5/2[422] orbital. This interchange reflects the mirror symmetry in nucleon configurations but also highlights the specific orbitals involved in the rotational dynamics. According to the TRS model [33, 64, 65] nucleons in high-j, low-Ω orbitals are more susceptible to pair breaking during rotation due to their strong coupling to the rotational axis and larger alignment gain when unpaired. Consequently, the breaking of nucleon pairs in these specific orbitals is likely responsible for the observed alignment and upbending in the MOIs. Understanding which orbitals contribute to the pair-breaking process provides valuable insights into the microscopic mechanisms driving rotational phenomena and the subtle differences between mirror nuclei in their response to increasing rotational frequency.

Figure 6. (color online) Calculated ground-state WS single-particle energy as a function of the quadrupole deformation

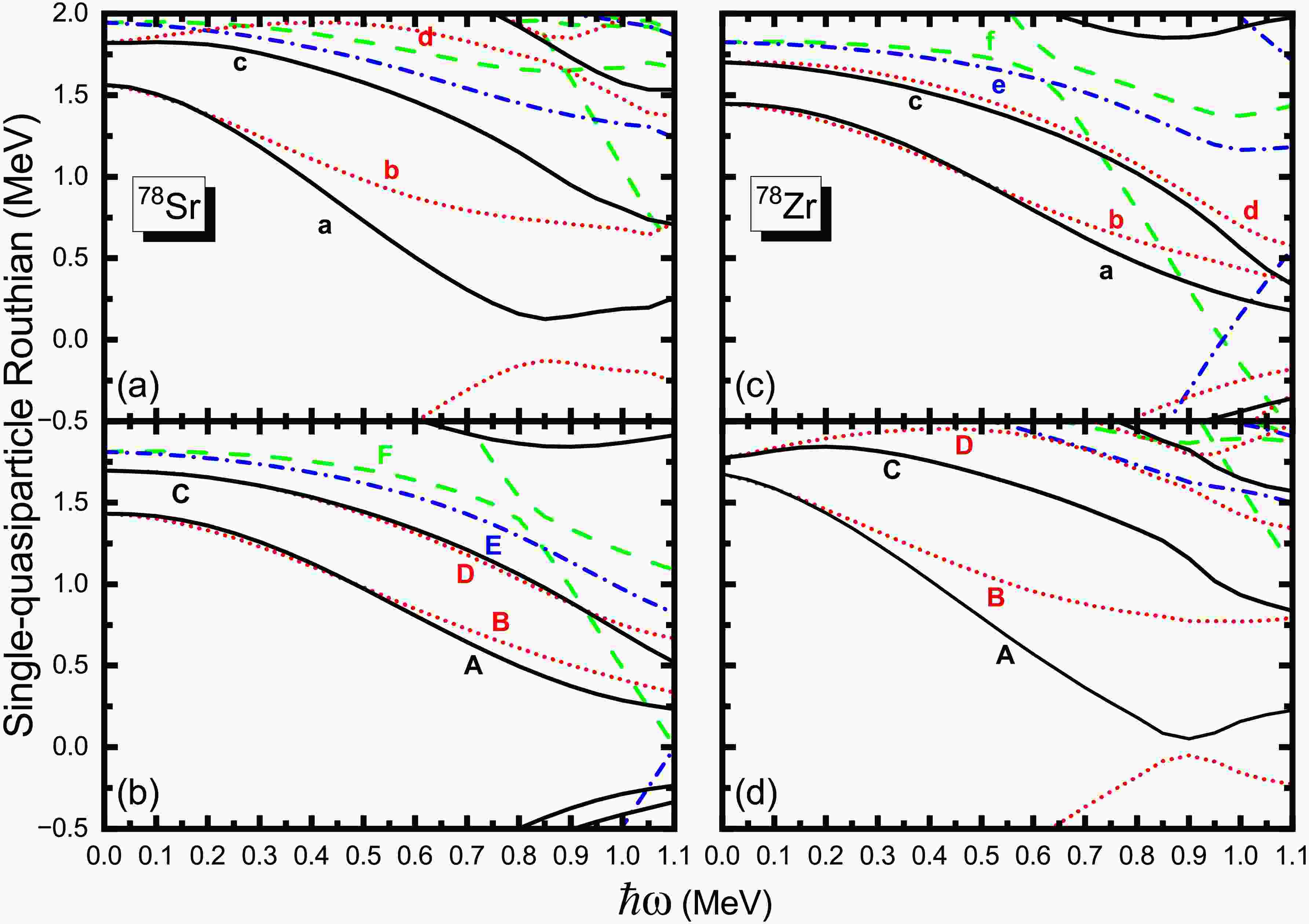

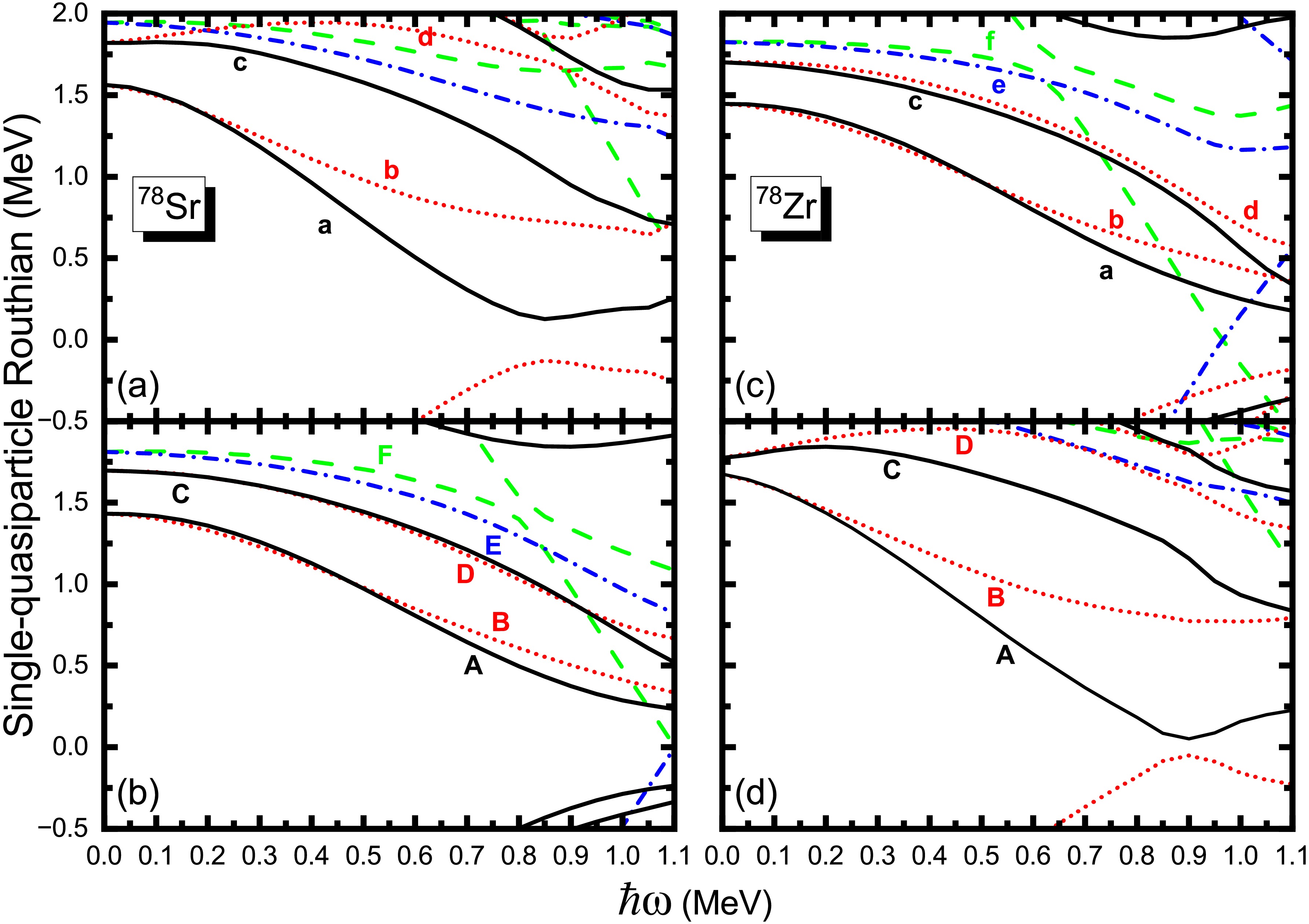

$\beta_2$ near the Fermi surface for the mirror nuclei 78Sr-78Zr. The positive (negative) parity levels are denoted by the black-solid (blue-dash) lines for protons (a,c) and neutrons (b,d), while the green-solid lines reveal the Fermi surface. Some single-particle orbits near the Fermi surface are labeled using Nilsson quantum numbers$\Omega \left[ Nn_z\Lambda \right]$ .The quasiparticle Routhian diagram plotted against rotational frequency provides a powerful and insightful tool for examining the intricate interplay between nuclear rotation and microscopic structural changes of mirror symmetry violation. In Fig. 7, we present the evolution of quasiparticle Routhian levels as a function of rotational frequency for the mirror nuclei 78Sr and 78Zr. The letters labelled in Tables 3 are followed with Ref. [66]. It is important to note that, unlike the band structure variations shown in Figs. 3, 4, and 5, which depict changes in the yrast states. Figure 7 specifically focuses on the microscopic quasiparticle configurations associated with the first upbending phenomenon. To this end, the calculations are conducted assuming a fixed prolate deformation with

$ \beta_2\approx0.40 $ , corresponding to the well-deformed rotational band. Beyond a rotational frequency of approximately 0.8 MeV, the prolate band with$ \beta_2\approx0.40 $ no longer represents the lowest-energy configuration (yrast band), indicating a structural change in the nucleus. The quasiparticle Routhian diagram reveals subtle but significant differences between these two mirror nuclei that arise from the distinct nuclear environments shaped by their proton and neutron compositions. Notably, the calculated neutron AB band crossing in 78Zr occurs slightly later than the proton ab band crossing in its mirror partner, 78Sr, which corresponds to the first upbending of the MOIs in Fig. 3. This temporal difference in the alignment frequency reflects the nuanced effects of the underlying nucleon interactions and shell structure. Though the Woods-Saxon potential parameters are indeed isospin-dependent, this naturally leads to differences in proton vs. neutron alignment patterns. This observation underscores the need for further theoretical and experimental investigations into the differences among neutron-neutron (nn), proton-proton (pp), and neutron-proton (np) interactions in mirror nuclei [47, 67]. Understanding how these pairing and residual interactions vary and influence the rotational response is essential for developing a comprehensive microscopic description of mirror symmetry breaking in nuclear structure. Future studies focusing on these interaction differences will help clarify the mechanisms driving the subtle asymmetries observed in the rotational behavior of mirror nuclei, thus advancing our knowledge of isospin-dependent nuclear dynamics.

Figure 7. (color online) The calculated results of the quasineutron and quasiproton energy levels of 78Sr (a,b) and 78Zr (c,d) as a function of the rotational frequency

$ \hbar\omega $ . The deformation is taken from the ground-state equilibrium deformation$ (\beta_2, \gamma, \beta_4) = (0.396, -3.2, -0.013) $ in 78Sr and (0.405,$-$ 2.5,$-$ 0.016), respectively. The parity and signature ($\pi,\alpha$ ) are: black solid line$ (+, +1/2) $ , red dotted line$ (+, -1/2) $ , blue dot-dashed line$ (-, +1/2) $ , and green dashed line$ (-, -1/2) $ . The letters marking the quasiparticle orbits are consistent with those in Tables 3.78Sr $(\pi,\alpha)_n$ Label (p) Single-particle orbit $(\pi,\alpha)_n$ Label (n) Single-particle orbit $(+, +1/2)_1$ a $1g_{9/2}[431]3/2$ $(+, +1/2)_1$ A $1g_{9/2}[422]5/2$ $(+, -1/2)_1$ b $1g_{9/2}[431]3/2$ $(+, -1/2)_1$ B $1g_{9/2}[422]5/2$ $(+, +1/2)_2$ c $1g_{9/2}[422]5/2$ $(+, +1/2)_2$ C $1g_{9/2}[431]1/2$ $(+, -1/2)_2$ d $1g_{9/2}[422]5/2$ $(+, -1/2)_2$ D $1g_{9/2}[431]1/2$ $(-, +1/2)_1$ E $1f_{5/2}[301]3/2$ $(-, -1/2)_1$ F $1f_{5/2}[301]3/2$ 78Zr $(\pi,\alpha)_n$ Label (p) Single-particle orbit $(\pi,\alpha)_n$ Label (n) Single-particle orbit $(+, +1/2)_1$ a $1g_{9/2}[422]5/2$ $(+, +1/2)_1$ A $1g_{9/2}[431]3/2$ $(+, -1/2)_1$ b $1g_{9/2}[422]5/2$ $(+, -1/2)_1$ B $1g_{9/2}[431]3/2$ $(+, +1/2)_2$ c $1g_{9/2}[431]1/2$ $(+, +1/2)_2$ C $1g_{9/2}[422]5/2$ $(+, -1/2)_2$ d $1g_{9/2}[431]1/2$ $(+, -1/2)_2$ D $1g_{9/2}[422]5/2$ $(-, +1/2)_1$ e $1f_{5/2}[301]3/2$ $(-, -1/2)_1$ f $1f_{5/2}[301]3/2$ Table 3. At

$\hbar\omega = 0$ , Labels used for the quasiproton (p) and quasineutron (n) states for parity π and signature α in 78Sr and 78Zr, with n denoting the nth such state. Single-particle orbits are labeled using the shell model and the Nilsson quantum number$\Omega \left[ Nn_z\Lambda \right]$ . -

In summary, we have systematically studied the collective properties in three pairs of mirror nuclei 74Kr-74Sr, 78Sr-78Zr and 82Zr-82Mo by using the pairing self-consistent TRS calculation in the (

$ \beta_2 $ , γ,$ \beta_4 $ ) deformation space. The well-deformed shape and shape coexistence are deduced in all cases. The ground states of the 74Kr-74Sr and 78Sr-78Zr mirror pairs are prolate; however, their secondary minima diverge between spherical and oblate configurations, suggesting a partial breaking of mirror symmetry. Although the 82Zr-82Mo mirror pair possesses spherical ground states, their third minima exhibit prolate deformation, which is consistent with experimental observations. Rotational properties show good agreement with experiments, including the upbending of the MOIs. Our findings predict that 74Kr-74Sr exhibit robust mirror symmetry in their rotational dynamics, whereas 78Sr-78Zr display earlier upbending compared to their mirror counterparts, indicating a possible manifestation of mirror symmetry breaking in these nuclei. Further analysis attributes the upbending primarily to a reduction in pairing correlations that leads to the breaking of nucleon pairs occupying high-j low-Ω orbitals. Single-particle energy level calculations identify the 1$ g_{9/2} $ orbitals near the Fermi surface as critical contributors to this alignment process. Additionally, the quasiparticle Routhian diagrams suggest that neutron band crossing in 78Sr precedes proton band crossing in 78Zr, revealing subtle differences in nuclear environments driven by proton and neutron configurations. These findings underscore the necessity for more detailed investigations into isospin-dependent nucleon interactions—namely nn, pp, and np correlations—to fully understand the mechanisms behind mirror symmetry breaking in nuclear rotational dynamics. We will extend this study to other pairs to explore mirror symmetry violation in the future work.

On the Prediction of Mirror Symmetry Violation in Rotational Properties for A ≈ 80 Nuclei

- Received Date: 2025-11-27

- Available Online: 2026-04-01

Abstract: Within the framework of the macroscopic-microscopic model by using total-Routhian-surface calculations in the three-dimensional space ($ \beta_2 $, γ, $ \beta_4 $), a systematic investigation of mirror-pair nuclei 74Kr-74Sr, 78Sr-78Zr, and 82Zr-82Mo has been carried out to predict the mirror symmetry violation in their rotational properties. The empirical P-factor, energy ratio $ R_{4/2} $, the energies of the first excited state $ E_{2_1^+} $, and the binding energies $ E_{\rm{bind}} $ of these mirror partner nuclei are displayed, together with the primary deformation $ \beta_2 $ and $ \beta_4 $. Our calculations indicate that shape coexistence exists in the ground state of all these mirror partner nuclei. The moments of inertia of these mirror partner nuclei are not always the same in the yrast band. The rotational frequencies at which upbending occurs in 74Kr and 74Sr are nearly identical, whereas in 78Sr and 82Zr the upbending sets in earlier than in their mirror partners 78Zr and 82Mo. The upbending phenomenon in 74Kr and 74Sr is attributed to the simultaneous alignment of proton and neutron. Taking the nuclei 78Sr-78Zr as examples, we suggest the first upbending is attributed to the alignment of protons and neutrons within the $ 1g_{9/2} $ orbitals, as evidenced by the calculated single-particle energy levels. These specific band crossings are further elucidated through quasiparticle Routhian diagrams, which characterize the alignment of high-j, low-Ω pairs and reveal the underlying microscopic mechanism. Our results show that 74Kr and 74Sr maintain strong mirror symmetry in their rotational behavior, 78Sr and 82Zr exhibit earlier upbending than their mirrors, indicating possible mirror symmetry breaking. This study may provide new insights for future research into the mirror symmetry violation in the nuclear excited states.

Abstract

Abstract HTML

HTML Reference

Reference Related

Related PDF

PDF

DownLoad:

DownLoad: