-

Through quantum effects, energy can be emitted from the horizon of a black hole in the form of Hawking radiation [1-3]. Thus, a black hole can be treated as an actual thermodynamic system, exhibiting traditional thermodynamical behavior [4]. This similarity has led to the definition of Bekenstein-Hawking entropy, which is proportional to the area of the event horizon [5-8]. Understanding this entropy production is crucial for quantifying black hole thermal systems. Such systems are important for comprehending the concepts of black hole physics, and they also serve to stimulate new research ideas. Recently, the relationships between gravitation, thermodynamics, and quantum theory have been attracting considerable attention.

A recent development in black hole thermodynamics has been the construction of an extended phase space within a black hole [9-11]. The idea is to treat the cosmological constant as the pressure of the black hole thermal system, with its thermodynamical volume being the thermodynamical conjugate of pressure; that is,

$ V = (\partial M/\partial P)|_{S,Q,J} $ [12, 13]. This volume is regarded as that enclosed by the event horizon of a black hole, and the gravitational mass is regarded as enthalpy rather than energy. Using this framework, many remarkable black hole characteristics have been studied, including Van der Waals behaviors [14], solid/liquid phase transitions and triple points [15], re-entrant phase transitions [16], holographic heat engines [17], and Joule-Thomson expansion [18]. This research field has been generalized as black hole chemistry (for a review, see [13]). In these studies, the four laws of thermodynamics play a significant role; thus, it is interesting and important to explicitly discuss their validity in the extended thermodynamical phase spaces of black holes.Furthermore, the first law's validity does not always entail that the second law and weak cosmic censorship conjecture (WCCC) are equally valid. The WCCC states that a singularity should be hidden by the event horizon (except at the Big Bang); thus, it is invisible to outside observers. Cosmic censorship was proposed to avoid the breakdown of causality [19-21]; it remains a well-known open problem. Thus, the validity of cosmic censorship is still an active discussion topic in black hole physics. One common method is to consider a particle being absorbed by a black hole, to determine whether the horizon still exists; if it does, this validates the WCCC (see, e.g., [22]) and its extension to other test fields [23-25]. Since its proposal, the WCCC has been widely studied for various black holes, through particle absorption and test field scattering techniques [26-32]. Previous studies have shown that the validity of the WCCC depends on both the state of the black hole and the perturbation method; thus, there is no general framework with which to discuss the conjecture.

More recently, Gwak investigated horizon variations and thermodynamical laws in the extended phase space for charged particle absorption; the validity of the WCCC was also verified [33]. It was shown that the second law of thermodynamics is violated by the

$ PV $ term's contribution, though the WCCC remains valid. This work was soon extended to other gravitational theories [34-46]. Here, we extend this work to include massive gravity, a theory that modifies gravity at large distance-scales.Black holes are important theoretical tools for exploring general theories of gravity, because they provide a practical environment for testing them. Moreover, the graviton is known to be massless in Einstein's theory of general relativity. More recently, cosmologists have proposed the idea of using a massive graviton to modify general relativity, to verify the theory's reliability. The first attempted construction of massive gravity was performed by Fierz and Pauli; however, their construction did not recover general relativity in the limit of

$m_{\rm graviton} = 0$ [47]. Later, Vainshtein proposed a nonlinear model for massive gravity [48]; however, it suffered from Boulware-Deser (BD) ghosts [49, 50]. More recently, greater numbers of nonlinear terms have been introduced into massive gravity to prevent this instability [51-60]. Various phenomenologies of massive gravity have been studied. In particular, its thermodynamical phase transitions (and the relevant studies in extended phase space) have been addressed in [61-75].In this paper, we revisit thermodynamics and the WCCC in four-dimensional massive gravity with a negative cosmological constant [61, 76]. First, we implement Gwak's proposal by considering a charged particle being absorbed by a black hole; then, as an alternative method, we consider a shell of dust falling into it.

This paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we briefly review the AdS black hole solution for massive gravity. In Section 3, we study the thermodynamics of massive-gravity black holes by considering the absorption of charged particles in both normal and extended phase spaces. In Section 4, we investigate the laws of thermodynamics for a shell of infalling dust. Finally, in Section 5, we focus on the WCCC under the charged-particle absorption, through which we demonstrate that the horizon always exists. Our discussion and conclusions are presented in Section 6.

-

The action of the four-dimensional massive gravity theory considered here is given by (in the units

$ c = G = \hbar = k_B = 4\pi \varepsilon_0 = 1 $ ) [76]$ S = \frac{1}{16\pi}\int {\rm d}^{4}x\sqrt{-g}\left[R+\frac{6}{l^2}-\frac{1}{4}F^2+m_g^2\sum_{i = 1}^4c_i{\cal{U}}_i(g,f)\right], $

(1) where

$ m_g $ is the graviton mass in the theory. In this equation, the last term represents the massive potentials associated with the graviton; these break the diffeomorphism invariance in the bulk theory and generate momentum relaxation in the dual boundary theory. The coupling parameters$ c_i $ are constants,$ f $ denotes the reference metric, and$ {\cal{U}}_i $ denote symmetric polynomials of the eigenvalues for the$ 4 \times 4 $ matrix$ {\cal{K}}^{\mu}_{\; \nu}\equiv\sqrt{g^{\mu\alpha}f_{\alpha\nu}} $ , which are expressed as$ \begin{array}{l} {\cal{U}}_1 = [{\cal{K}}],\; \; \; {\cal{U}}_2 = [{\cal{K}}]^2-[{\cal{K}}^2],\\ {\cal{U}}_3 = [{\cal{K}}]^3-3[{\cal{K}}][{\cal{K}}^2]+2[{\cal{K}}^3],\\ {\cal{U}}_4 = [{\cal{K}}]^4-6[{\cal{K}}^2][{\cal{K}}]^2+8[{\cal{K}}^3][{\cal{K}}]+3[{\cal{K}}^2]^2-6[{\cal{K}}^4], \end{array} $

(2) where

$ [{\cal{K}}] = {\cal{K}}^{\mu}_{\; \mu} $ and the square root in$ {\cal{K}} $ is defined as$ (\sqrt{{\cal{K}}})^{\mu}_{\; \nu}(\sqrt{{\cal{K}}})^{\nu}_{\; \lambda} = {\cal{K}}^{\mu}_{\; \lambda} $ .The static spherical black hole solution of the above action yields [61]

$ {\rm d}s^2 = -f(r){\rm d}t^2+\frac{{\rm d}r^2}{f(r)}+r^2({\rm d}\theta^2+\sin^2\theta {\rm d}\varphi^2). $

(3) Following [76], we take the reference metric as

$ f_{\mu\nu} = \mathrm{diag}(0,0,c_0^2h_{ij}) $ . Then, combining this with the ansatz (Eq. (3)), we obtain$ {\cal{U}}_1 = 2c_0/r $ ,$ {\cal{U}}_2 = 2c_0^2/r^2 $ , and$ {\cal{U}}_3 = {\cal{U}}_4 = 0 $ ; thus, the field solutions are$F_{\mu\nu} = \partial_{\mu}A_{\nu}-\partial_{\nu}A_{\mu},\; \; \; A = -\frac{q}{r} {\rm d}t, $

(4) $f(r) = 1+\frac{r^2}{l^2}-\frac{2{\cal{M}}}{r}+\frac{q^2}{r^{2}}+\frac{c_0c_1m_g^2}{2}r+c_0^2c_2m_g^2. $

(5) According to the Hamiltonian approach, the parameters

$ {\cal{M}} $ and$ q $ relate to the mass and charge of the black hole as [61]$ M = \frac{V_2}{4\pi}{\cal{M}}, \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; Q = \frac{V_2}{4\pi}q , $

(6) where

$ V_2 $ is the volume of the two-dimensional space. Using$ f(r)|_{r = r_h} = 0 $ , where$ r_h $ denotes the horizon radius, we derive the mass as$ M = \frac{r_h}{2}+\frac{q^2}{2r_h}+\frac{1}{2}c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2 r_h +\frac{1}{4}c_0 c_1 m_g^2 r_h^2+\frac{r_h^3}{2 l^2} . $

(7) The Hawking temperature and entropy of the black hole are

$ T = \frac{f'(r_h)}{4\pi} = \frac{\ c_0 c_1 m_g^2}{4\pi}+\frac{1}{4\pi r_h} +\frac{c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2}{4 \pi r_h}-\frac{q^2}{4\pi r_h^3}+\frac{3r_h}{4\pi l^2}, $

(8) $ S = \int_0^{r_h} {\rm d}r \frac{1}{T}\left(\frac{\partial M}{\partial r}\right)_{q,l,c_i} = \pi r_h^2, $

(9) respectively.

The thermodynamics of massive black holes have been studied in [61-75]. Here, we study the thermodynamics of massive gravity black holes using two methods: one in which the black hole absorbs a charged particle and one in which a shell of dust falls into the black hole. We primarily focus on the validity of the thermodynamical laws in both the normal and extended phase spaces.

-

In this section, we study the thermodynamics of massive gravity black hole, by considering their absorption of a charged particle.

-

If we assume that a charged, massive-gravity black hole is perturbed by absorbing a charged particle, then its mass, charge, and AdS radius (which relates to the thermodynamic pressure and volume) can be shifted. During the process, changes to the black hole's conserved quantities are identical to those of the charged particle. Thus, the relation between the conserved quantities of the black hole following particle absorption can be simultaneously obtained by analyzing the corresponding relations of the particle. We start with the Hamiltonian of the charged particle,

$ {\cal{H}} = \frac{1}{2}g^{\mu\nu}(P_\mu-e A_\mu)(P_\nu-e A_\nu), $

(10) and the Hamiltonian-Jacobi action,

$ S = \frac{1}{2}m^2 \lambda-E t+L\phi+S_r(r)+S_\theta(\theta), $

(11) where the four-momentum

$ P_\mu $ of the particle is defined as$ P_\mu = \partial_\mu S $ . Here,$ m^2 $ ,$ e $ , and$ \lambda $ denote the mass and charge of the particle and an affine parameter, respectively. Because of the symmetry of the metric (Eq. (3)), the quantities$ E $ and$ L $ are conserved with respect to$ t $ and$ \varphi $ and denote the energy and angular momentum of the particle, respectively. To proceed, we combine Eq. (3) with Eqs. (10-11) to deduce$\begin{split} m^2&-f(r)^{-1}(-E-e A_t)^2+f(r)\Big(\partial_{r}S_r(r)\Big)^2\\&+r^{-2}\Big((\partial_{\theta}S_\theta)^2+\sin^{-2}{\theta}L^2\Big) = 0. \end{split} $

(12) The angular term of the above expression can be defined separately as

$ \begin{split} K \equiv& \Big(\partial_{\theta}S_\theta(\theta)\Big)^2+\sin^{-2}{\theta}L^2 = -m^2 r^2\\&+\frac{r^2}{f(r)}(-E-e A_t)^2-r^2 f(r)\Big(\partial_{r}S_r(r)\Big)^2. \end{split} $

(13) Thus, Eq. (11) is rewritten as

$ S = -E t+L\phi+\int{{\rm d}r}\sqrt{R}+\int{{\rm d}\theta}\sqrt{\Theta}, $

(14) where

$ S_r\equiv\int{{\rm d}r}\sqrt{R},\; \; S_\theta\equiv\int{{\rm d}\theta}\sqrt{\Theta},\; \; \Theta\equiv K-\sin^{-2}{\theta}L^2, $

(15) $ R = \frac{1}{r^2f(r)}(-K^2-u^2r^2)+\frac{1}{r^2f(r)}\left(\frac{r^2}{f(r)}(-E-e A_t)^2 \right). $

(16) Subsequently, the radial momentum

$ P^r $ and angular momentum$ P^\theta $ can be computed as$ P^r = g^{rr}\partial_{r}S_r(r) = f(r)\sqrt{\frac{-K-m^2 r^2}{r^2 f(r)}+\frac{(-E-eA_t)^2}{f^2(r)}}, $

(17) $ P^\theta = g^{\theta\theta}\partial_{\theta}S_\theta(\theta) = \frac{1}{r^2}\sqrt{K-\frac{1}{\sin^2{\theta}}L^2}. $

(18) Following [33], we assume that the charged particle is completely absorbed by the black hole upon passing through the outer horizon. As a result, it is impossible for an observer outside the horizon to distinguish the conserved quantities of the particle from those of the black hole. In particular, a relationship between the conserved quantities and momenta at any radial position can be derived. Then, the limit (Eq. (17)) at the outer horizon gives us the following relation between the conserved quantities and radial momenta:

$ E = \frac{q}{r_h} e+|P^r|. $

(19) The above equation implies that both the momentum and electric charge of the particle contribute to the energy. For simplicity, we hereafter denote

$ |P^r| $ as the radial momentum at the horizon. We note that$ q/r_h $ is the electromagnetic potential at the event horizon. To ensure that the particle flows into the black hole in a positive flow of time,$ |P^r| $ should be positive. When electrical attraction acts upon the particles, their total energy can be negative. Here, we simply choose the signs in front of$ E $ and$ |P^r| $ to be positive, as was performed in [33, 36, 37, 77].The relation concerns the interactions between the particle and the black hole, and we assume that no energy is lost during the process. Namely, the charge of the particle

$ e $ is equal to the charge variation${\rm d}Q$ of the black hole. In Eq. (19), the energy of the particle is expressed in terms of$ e $ and$ |P^r| $ near the horizon. We must find a corresponding thermodynamical term that also contains the variation of$ e $ and$ |P^r| $ . Following Gwak [33], we assume that the energy of the charged particle changes the internal energy of the black hole as it is absorbed. Here, we check the validity of the thermodynamical laws in both the normal and extended phase spaces, under the assumption that$E = {\rm d}U$ . -

We first study the validity of the thermodynamical laws for massive black holes in the normal phase space; in such spaces, the mass of the black hole represents its internal energy; thus, with the assumption of

$E = {\rm d} U$ , Eq. (19) can be rewritten as$ E = {\rm d} U = {\rm d} M = \frac{q}{r_h}e+ |P^r|. $

(20) To analyze the first law under particle absorption, we rewrite the variation of entropy from the Bekenstein's area law as

${\rm d}S_h = 2\pi r_h {\rm d}r_h$ . The event horizon variation${\rm d}r_h$ is determined by the charge, energy, and radial momentum of the absorbed particle and directly contributes to the changes of the function$ f(r) $ . Then, the change of$ f(r) $ results in a relocated event horizon$r_h+{\rm d}r_h$ . More explicitly, we can express the difference between the initial state$ f(M,Q,r_h) $ and final state$f(M+ {\rm d}M, Q+{\rm d}Q,r_h+{\rm d}r_h)$ as$\begin{split} & f(M+{\rm d}M,Q+{\rm d}Q,r_h+{\rm d}r_h)-f(M,Q,r_h) \\=& \frac{\partial{f_h}}{\partial{M}}{\rm d}M+\frac{\partial{f_h}}{\partial{Q}}{\rm d}Q+ \frac{\partial{f_h}}{\partial{r_h}}{\rm d}r_h, \end{split}$

(21) where

${\rm d}M,{\rm d}Q,{\rm d}r_h$ represent the variation of the charge, energy, and horizon of the black hole, respectively. At the event horizon,$ f(M,Q,r_h) = 0 $ and$f(M+{\rm d}M, Q+{\rm d}Q, r_h+{\rm d}r_h) = 0$ should be satisfied; thus, we deduce that${\rm d}f(r_h) = {\rm d}f_h = 0$ ; that is,$ {\rm d}f_h = \frac{\partial{f_h}}{\partial{M}}{\rm d}M+\frac{\partial{f_h}}{\partial{Q}}{\rm d}Q+ \frac{\partial{f_h}}{\partial{r_h}}{\rm d}r_h = 0. $

(22) Using Eqs. (20) and (22), we can obtain

${\rm d}r_h$ and thereby${\rm d}S_h$ , as$ {\rm d}S_h = \frac{24 \pi |P^r| r^3_h}{3 c_0 c_1 m_g^2 r^3_h+12 M r_h+12 r^4_h/l^2-12 q^2}. $

(23) Combining Eqs. (8) and (23) gives us the relation

$T{\rm d}S_h = |P^r|$ . With this, Eq. (19) becomes$E = e\; q/r_h + T{\rm d}S_h$ . Subsequently, because$E = {\rm d}M$ and$e = {\rm d}Q$ , we obtain the form of the variation as$ {\rm d}M = T{\rm d}S_h+\Phi {\rm d}Q, $

(24) which is the first law of thermodynamics for massive black holes in normal phase space.

Next, we use Eq. (23) to check the validity of the second law of the thermodynamics, which states that the entropy must increase after particle absorption.

First, for the case of the extremal massive black hole (in which the temperature vanishes), applying

$ T = 0 $ in Eq. (8) gives us the marginal mass$ M_e = r_e+c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2 r_e+\frac{3}{4}c_0 c_1 m_g^2 r_e^2+2 r_e^3/l^2, $

(25) where

$ r_e $ denotes the horizon of the extremal black hole and can be readily reduced as a function of$ q, l, c_0, c_1 $ , and$ c_2 $ ; we omit these steps here for simplicity. Substituting Eq. (25) into (23), we deduce that${\rm d}S_h = \infty$ holds for the extremal black hole.In the case of a non-extremal black hole,

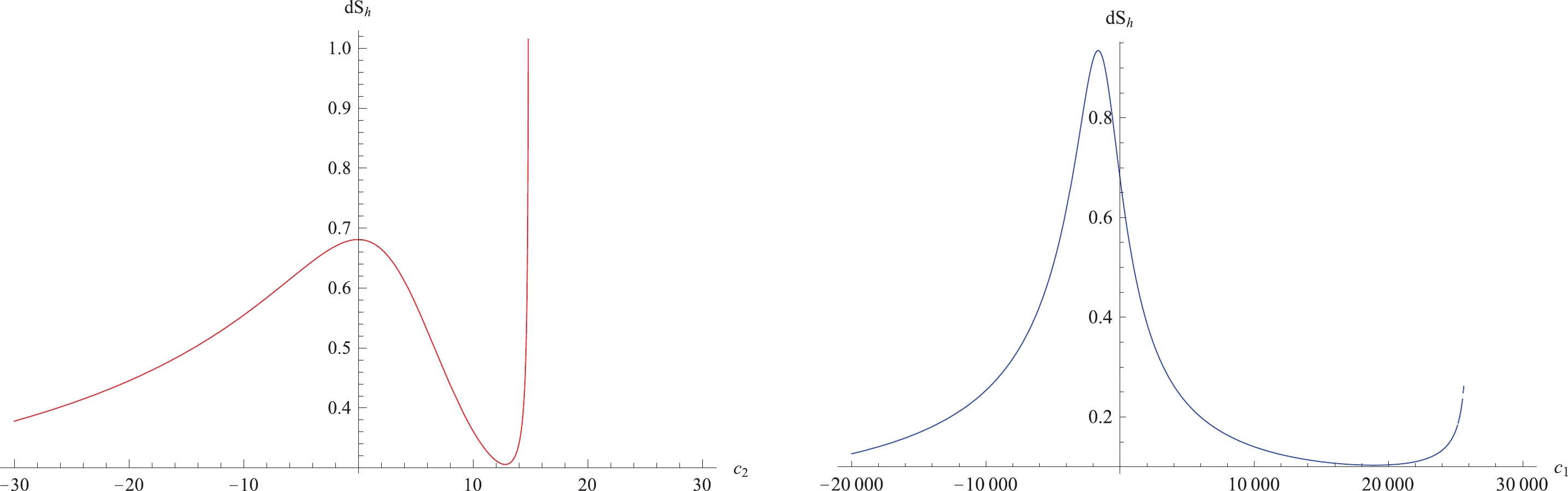

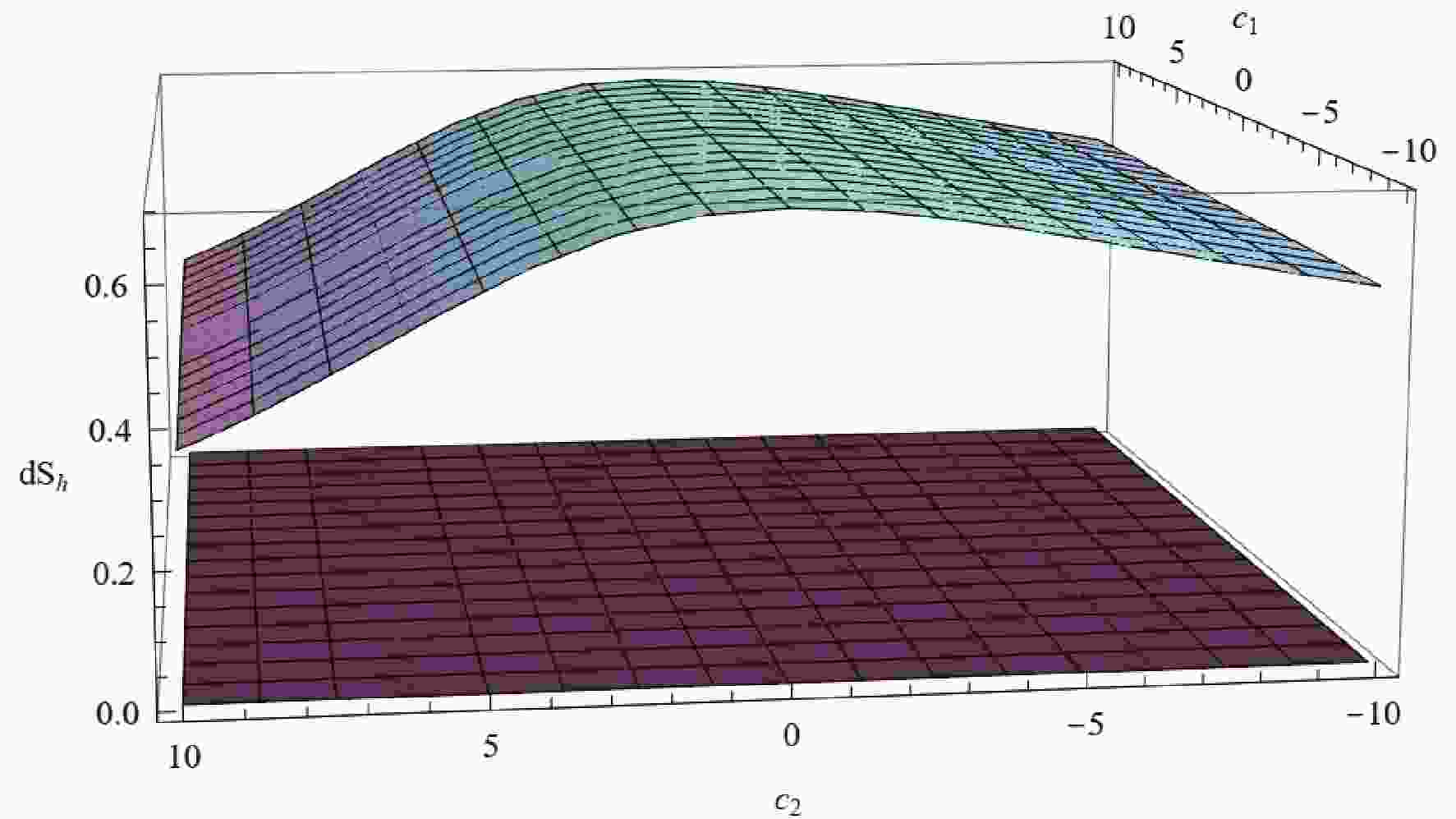

${\rm d}S_h$ remains positive for any$ c_i(i = 1,2) $ . We plot the relation between${\rm d}S_h$ and the values of$ c_i $ in Fig. 1. It can be seen that the value of${\rm d}S_h$ always exceeds zero. More explicit relations between${\rm d}S_h$ and$ c_1,c_2 $ are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 1. (color online)

${\rm d}S_h$ near the horizon with respect to$ c_1,c_2 $ for a non-extremal black hole in normal phase space.

Figure 2. (color online) (left) the relationship between

${\rm d}S_h$ and$ c_2 $ with fixed$ c_1 = 5 $ ; (right) the relationship between${\rm d}S_h$ and$ c_1 $ with fixed$ c_2 = 5 $ .Thus, the variation of entropy is always positive in the normal phase space. Expressed otherwise, the second law of thermodynamics is valid in the normal phase space under particle absorption. In the next subsection, we consider the case for the

$ PV $ term. -

The PV criticality, characterized by treating the pressure as

$ P = 3/8\pi l^2 $ , has been studied in [62-64]. Here, we briefly review the main properties of the extended phase space; then, we check the validity of the thermodynamical laws under the absorption of a charged particle.In the extended phase space, the corresponding conjugate quantity of the pressure

$ P = 3/8\pi l^2 $ is treated as volume$ V $ [9,10]. Then, the mass (Eq. (7)) and temperature (Eq. (8)) are respectively rewritten as$ M = \frac{r_h}{2}+\frac{q^2}{2r_h}+\frac{1}{2}c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2 r_h +\frac{1}{4}c_0 c_1 m_g^2 r_h^2+\frac{4}{3}P \pi r_h^3 , $

(26) $ T = \frac{\ c_0 c_1 m_g^2}{4\pi}+\frac{1}{4\pi r_h} +\frac{c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2}{4 \pi r_h}-\frac{q^2}{4\pi r_h^3}+2 P r_h, \; \; \; \; S = \pi r_h^2. $

(27) The other conjugate quantities of the intensive parameters

$ P,Q,c_1 $ , and$ c_2 $ are$\begin{split} V =& \frac{\partial M}{\partial P} = \frac{4}{3}\pi r_h^3, \; \; \; \Phi = \frac{\partial M}{\partial Q} = \frac{q}{r_h},\; \;\\ A =& \frac{\partial M}{\partial c_1} = \frac{c_0 m_g^2 r_h^2}{4},\; \; B = \frac{\partial M}{\partial c_2} = \frac{c_0^2 m_g^2 r_h}{2},\end{split} $

(28) respectively, where we consider the coupling constants

$ c_1 $ and$ c_2 $ as thermodynamical variables. Here, the conjugate variables$ V $ ,$ A $ and$ B $ are defined by the differential of the enthalpy$ M $ . It is noticed that Kastor and Ray defined the thermodynamic conjugate variable in terms of a Killing potential in [9]; And the Hamiltonian method was applied to study the normal thermodynamics in massive gravity in [61]. It would be interesting to develop an alternative method to define those thermodynamical variables and understand their deep physics in our model. We hope to address this topic in the future. All thermodynamical quantities satisfy the extended first law of thermodynamics$ {\rm d}M = T{\rm d}S+\Phi {\rm d}Q+V {\rm d}P+A {\rm d}c_1+B {\rm d}c_2, $

(29) and the generalized Smarr relation is

$ M = 2TS-2VP+\Phi Q-A c_1. $

(30) We note that in the extended phase space,

$ M $ plays the role of enthalpy rather than the internal energy of the thermodynamical system; that is, we have$ M = U+VP+A c_1+B c_2. $

(31) In this case, the energy flux entering the event horizon will alter the internal energy of the black hole, which can be given as a function

$ U(Q,S,V,c_1,c_2) $ . From Eq. (31), the conserved energy and charge of the particle are$ E = {\rm d}U = {\rm d}(M-PV-A c_1-B c_2),\; \; \; \; \; e = {\rm d}Q. $

(32) Consequently, the energy relation near the horizon (Eq. (19)) can be expressed as

$ {\rm d}U = \frac{q}{r_h} {\rm d}Q+|P^r|. $

(33) Similar to the analysis of the previous subsection, the slight variations of the redshift function are

$\begin{split} {\rm d}f_h =& \frac{\partial{f_h}}{\partial{M}}{\rm d}M+\frac{\partial{f_h}}{\partial{Q}}{\rm d}Q+\frac{\partial{f_h}}{\partial{P}}{\rm d}P \\&+ \frac{\partial{f_h}}{\partial{r_h}}{\rm d}r_h+\frac{\partial{f_h}}{\partial{c_1}}{\rm d}c_1+\frac{\partial{f_h}}{\partial{c_2}}{\rm d}c_2 = 0. \end{split}$

(34) By combining Eqs. (31) and (34), the contributions of the

${\rm d}P,{\rm d}M,{\rm d}c_1$ , and${\rm d}c_2$ terms can be directly eliminated; thus, the above expression gives us$ {\rm d}r_h = \frac{12(c_1 {\rm d}A+c_2 {\rm d}B+|P^r|) r_h}{-12M +r_h(12 +12c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2 +9 c_0 c_1 m_g^2 r_h+16 P\pi r_h^2)}. $

(35) Subsequently, we obtain the change of entropy and volume as

$ {\rm d}S = \frac{24\pi(c_1 {\rm d}A+c_2 {\rm d}B+|P^r|) r_h^2}{-12M +r_h(12 +12c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2 +9 c_0 c_1 m_g^2 r_h+16 P\pi r_h^2)}, $

(36) $ {\rm d}V = \frac{16\pi(c_1 {\rm d}A+c_2 {\rm d}B+|P^r|) r_h^3}{-12M +r_h(12 +12c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2 +9 c_0 c_1 m_g^2 r_h+16 P\pi r_h^2)}. $

(37) From the aforementioned formulas and related thermodynamical quantities, we obtain the relation

$ T {\rm d}S-P {\rm d}V-c_1 {\rm d}A-c_2 {\rm d}B = |P^r|. $

(38) Thus, the expression of the internal energy in Eq. (32) becomes

$ {\rm d}U = \Phi {\rm d}Q+T {\rm d}S-P {\rm d}V-c_1 {\rm d}A-c_2 {\rm d}B, $

(39) then, combining Eqs. (31) and (39) gives

$ {\rm d}M = T{\rm d}S+\Phi {\rm d}Q+V {\rm d}P+A {\rm d}c_1+B {\rm d}c_2, $

(40) which is simply the first law of thermodynamics (Eq. (29)) for a massive black hole in the extended phase space. Expressed otherwise, the first law of thermodynamics holds in the extended phase space under particle absorption.

The next step is to analyze the sign of Eq. (36), to verify that the second law is valid in the extended phase space.

Taking the derivatives of

$ A $ and$ B $ with respect to$ r_h $ in Eq. (28) gives us${\rm d}A = c_0 m_g^2 r_h/2 {\rm d}r_h, {\rm d}B = c_0^2 m_g^2/2 {\rm d}r_h$ ; then, substituting these into Eq. (36) gives us$ {\rm d}S = \frac{24\pi|P^r| r_h^2}{-12M+r_h(12+6c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2+3c_0 c_1 m_g^2 r_h+16 P\pi r_h^2)}. \\ $

(41) Because the numerator of the above expression for

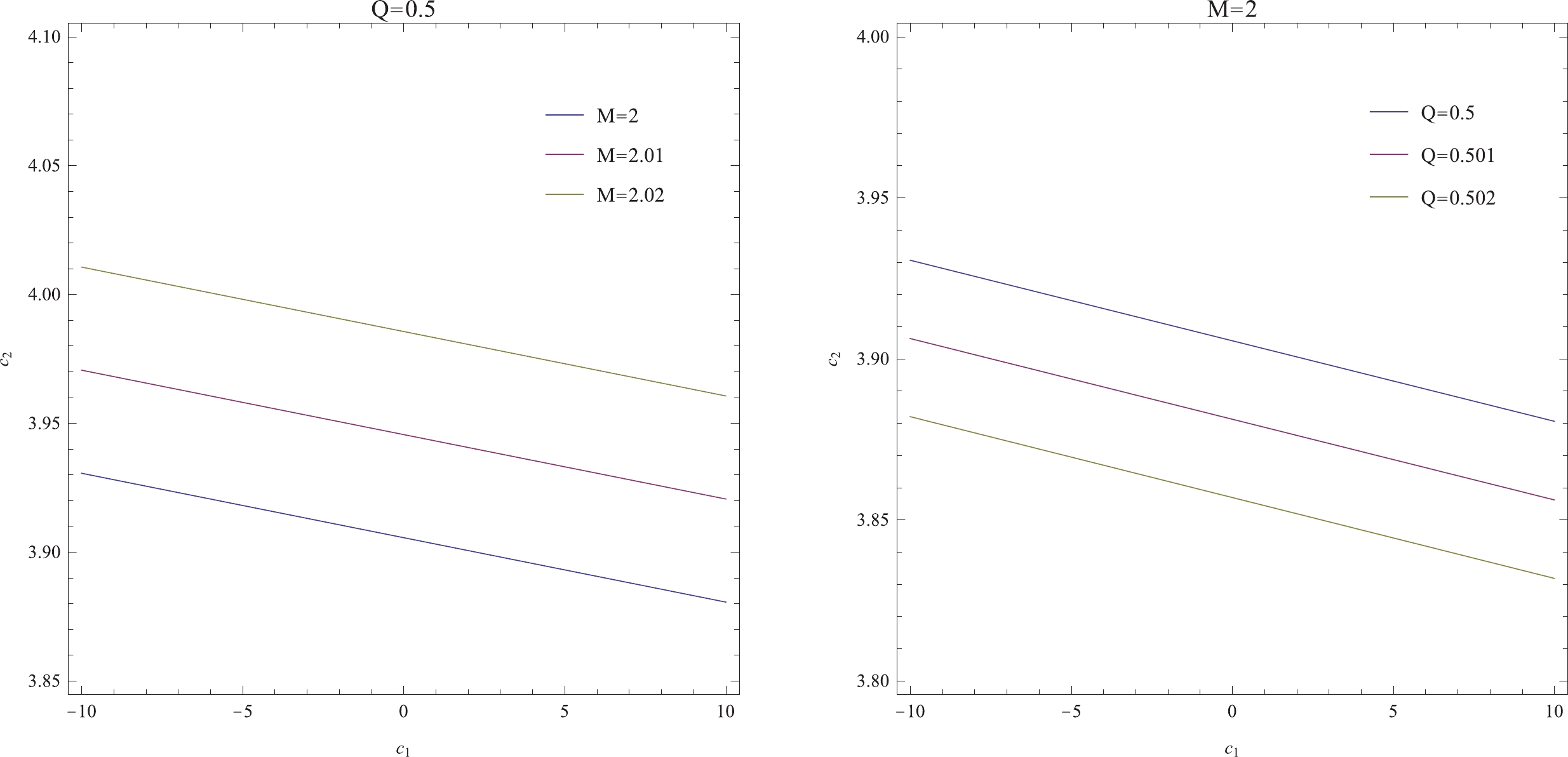

${\rm d}S$ is always positive, we must consider only the sign of the denominator, which we label as$ \Delta S_1 $ . The value of$ \Delta S_1 $ depends on the model parameters$ c_1 $ and$ c_2 $ . As a trial, we set$ c_0 = 100,m_g = 0.01,p = 1,P^r = 1 $ and list the values of$ \Delta S_1 $ for different$ c_2 $ under a fixed value of$ c_1 = 5 $ in Table 1. It can be seen that certain values of$ c_2 $ convert the sign of$ \Delta S_1 $ from positive to negative as it increases. Moreover, in Fig. 3, we plot the boundary lines$ (c_{1c},c_{2c}) $ for which$ \Delta S_1\to 0 $ . Hence, for parameters below the lines,$ \Delta S_1 $ is always positive, which indicates that the second law of thermodynamics is maintained; however, for the parameters above each line, one always obtains$ \Delta S_1< 0 $ , which implies a violation of the second law. It is also evident from the figure that the borderline depends upon$ M $ and$ Q $ , and that the parameter range in which the the second law is maintained is narrower for smaller$ M $ but bigger$ Q $ .$ M $

$ Q $

$ c_1 $

$ c_2 $

$ r_h $

$ \Delta S_1 $

2 0.5 5 3.6931 0.5099 0.1171 2 0.5 5 3.7931 0.5049 0.0587 2 0.5 5 3.8931 0.5 $ 2.88058\times10^{-6} $

2 0.5 5 3.9931 0.4951 -0.0589 2 0.5 5 4.0931 0.4903 -0.1181 Table 1. Numerical results of

$ \Delta S_1 $ for different$ c_2 $ under fixed$ c_1 = 5 $ .

Figure 3. (color online) The diagrams of critical

$ c_1 $ and$ c_2 $ values for different$ M $ (left) and$ Q $ values (right).Notably,

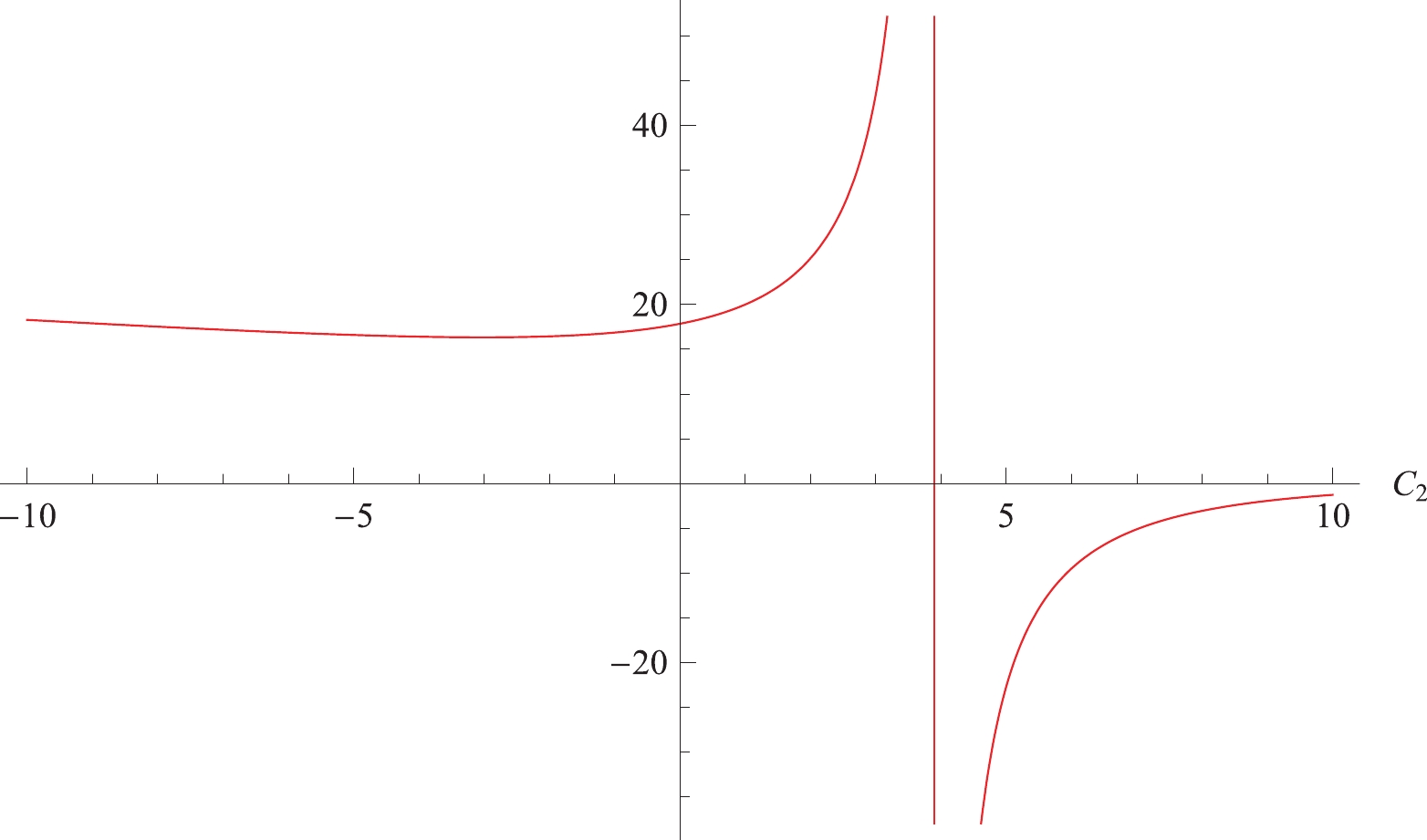

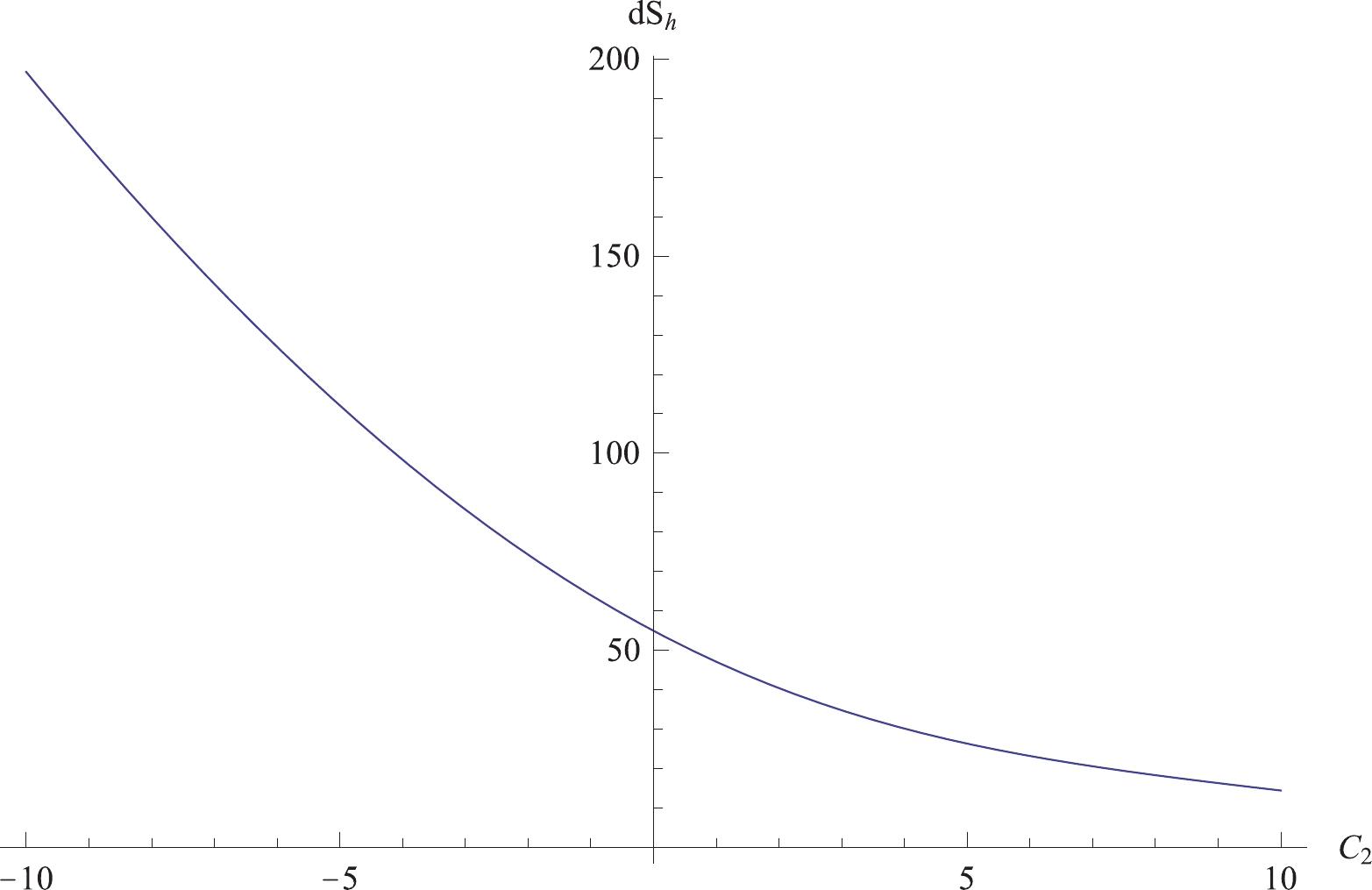

$ \Delta S_1 = 0 $ indicates that the change of entropy${\rm d}S$ diverges at the points$ (c_{1c},c_{2c}) $ on the critical line. Expressed otherwise, for a given$ c_1 $ , there exists a certain$ c_{2c} $ that brings about the divergence of${\rm d}S$ , as shown in Fig. 4. However, this is a trivial result because the important information is contained within the change of sign in${\rm d}S$ . Furthermore, the number of degrees of freedom is maximized as$ c_2 $ approaches$ c_{2c} $ , which is denoted by the vertical line in the figures. In fact, the critical point of$ c_2 $ is non-physical; as such, the black hole will not reach this point because it violates the second law of thermodynamics.

Figure 4. (color online)

${\rm d}S$ with$ M = 2, Q = 0.5, c_1 = 5 $ near the critical point$ c_{2c} $ .Here, we consider the case of the extremal massive black hole. We substitute the marginal mass (Eq. (25)) into Eq. (41); thus, we obtain

$ {\rm d}S_{\rm extremal} = -\frac{4\pi |P^r| r_e}{c_0 c_1 m_g^2 r_e+c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2+8\pi P r_e^2}. $

(42) Because the denominator of

${\rm d}S_{\rm extremal}$ is always positive, we follow the strategy used in the non-extremal case and define the numerator as$ \Delta S_2 $ . For the fixed values$ c_0 = 100, m_g = 0.01, p = 1, q = 1/2 $ , we list the numerical result of$ \Delta S_2 $ in Table 2. The result is similar to the case described above, which states that the violation of the second law of thermodynamics depends on the model parameters.$ c_1 $

$ c_2 $

$ r_e $

$ \Delta S_2 $

−2 −6.07319 0.493109 −0.0833 −2 −6.17319 0.49656 −0.0414 −2 −6.27319 0.5 $ 1.93433\times10^{-6} $

−2 −6.37319 0.50343 0.0410 −2 −6.47319 0.506849 0.0816 Table 2. Numerical results of

$ \Delta S_2 $ for different$ c_2 $ under fixed$ c_1 = -2 $ in the extremal case.Here, we briefly summarize the results obtained for the absorption of a charged particle by a massive black hole. (i) Both the first and second laws of thermodynamics hold in the normal phase space. (ii) When we consider the extended thermodynamics case by introducing the

$ PV $ term, the first law is always saved but the second law can be violated depending on the model parameters. This violation may be brought about by the assumption that the internal energy of the black hole is equal to the energy of the particle.In the next section, as an alternative strategy to particle absorption, we consider a thin shell falling into the massive black hole. We calculate the mass of the shell when it arrives at the horizon of the black hole and then revisit the validity of the laws of thermodynamics in both the extended and normal phase spaces.

-

By considering a thin shell approaching the horizon and using the techniques presented in Appendix A, we obtain the external surface of the shell in terms of

$ (M,Q,P,r,c_1,c_2) $ $ n_{r}^+ = \frac{ \left(1+\dfrac{8\pi P}{3}r^2-\dfrac{2}{r}+\dfrac{Q^2}{r^{2}}+\dfrac{c_0c_1m_g^2}{2}r+c_0^2c_2m_g^2+\dot{R}\right)^\frac{1}{2}}{ 1+\dfrac{ 8\pi P}{3}r^2-\dfrac{2M}{r}+\dfrac{q^2}{r^{2}}+\dfrac{c_0c_1m_g^2}{2}r+c_0^2c_2m_g^2}, $

(43) and the internal surface of the shell is denoted in terms of

$(M+{\rm d}M, Q+{\rm d}Q,$ $ P+{\rm d}P,r+{\rm d}r,c_1+{\rm d}c_1,c_2+{\rm d}c_2)$ $\begin{split} n^{r-} =& -\left(1-\frac{2(M+{\rm d}M)}{r}+\frac{(Q+{\rm d}Q)^2}{r^2}+\frac{8\pi (P+{\rm d}P)}{3}r^2\right.\\&\left.+\frac{c_0(c_1+{\rm d}c_1)m_g^2}{2}r +c_0^2(c_2+{\rm d}c_2)m_g^2+\dot{R}^2\right)^\frac{1}{2}. \end{split}$

(44) Subsequently, as the shell approaches the horizon, its mass can be calculated using

$ \begin{split} \mu =& -R(n^{r+}-n^{r-}) = -R \left(1+\frac{8\pi P}{3}r^2-\frac{2M}{r}\right.\\&\left.+\frac{Q^2}{r^{2}}+\frac{c_0c_1m_g^2}{2}r+c_0^2c_2m_g^2+\dot{R}^2\right)^\frac{1}{2}\\& - R\left(1-\frac{2(M+{\rm d}M)}{r}+\frac{(Q+{\rm d}Q)^2}{r^2}+\frac{8\pi (P+{\rm d}P)}{3}r^2\right.\\&\left.+\frac{c_0(c_1+{\rm d}c_1)m_g^2}{2}r+c_0^2(c_2+{\rm d}c_2)m_g^2+\dot{R}^2\right)^\frac{1}{2}, \end{split} $

(45) where

${\rm d}P$ denotes the variation of the shell's pressure. To vary the values of${\rm d}c_1$ and${\rm d}c_2$ , we can interpret them as special charges, labeled$ Q_{c_1} $ and$ Q_{c_2} $ , respectively. The terms containing$ c_1 $ and$ c_2 $ in the above equation above can be treated as a special form of energy, similar to the charge$ Q $ .To ensure that the particle does not recoil to outside the horizon and falls into the black hole successfully, the absorption condition, stipulating that the energy of the thin shell of dust must exceed a minimum threshold value, should be satisfied. Using the condition

$ n^{r+}-n^{r-}\geqslant 0 $ , the minimum energy can be derived as$ {\rm d}M\geqslant \frac{q {\rm d}Q}{r}+\frac{{\rm d}^2Q}{2r^2}, $

(46) where the second term is the negligible self-interaction of the particle. In Eq. (45), we have

$\dot{R} = {\rm d}R/{\rm d}\tau = u^r$ ; thus, we can solve for$ M $ and calculate the variation as$\begin{split} {\rm d}M =& \frac{1}{2} c_0^2 m_g^2 r {\rm d}c_2+\frac{1}{4} c_0 m_g^2 r^2 {\rm d}c_1\\&+\frac{4}{3} \pi r^3 {\rm d}P+\frac{({\rm d}Q)^2}{2r}+\frac{ Q }{r}{\rm d}Q-\frac{\mu ^2}{2 r}+\mu n^r . \end{split} $

(47) Here,

$ n^r = \sqrt{1+c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2+\frac{1}{2}c_0 c_1 m_g^2 r-\frac{2 M}{r}+\frac{8}{3}\pi P r^2+\frac{Q^2}{r^2}+\dot{R}^2}, $

(48) where

$ \mu $ and$ n^r $ denote the rest mass and radial velocity of the shell, respectively. We take the latter as a positive value, to ensure that the shell arrives at the black hole horizon. The higher orders of$ \mu $ and${\rm d}Q$ represent the self-interactions of particles and can be neglected in the current context. Thus, Eq. (45) can be re-written as$\begin{split} {\rm d}M = & \frac{4}{3} \pi r^3 {\rm d}P+\frac{ Q {\rm d}Q }{r}+\frac{1}{4} c_0 m_g^2 r^2 {\rm d}c_1\\&+\frac{1}{2} c_0^2 m_g^2 r {\rm d}c_2+\mu n^r . \end{split}$

(49) Here, we discuss the thermodynamical properties under a variation of mass, as calculated using the shell in the extended phase space. The increase in energy relates to the black hole's mass. Hence, we can discuss the violation of thermodynamics using the expression of

${\rm d}r_h$ , which can be found by inserting Eq. (49) into (34). Then, we can delete${\rm d}M$ directly. Interestingly,${\rm d}Q,{\rm d}c_1,{\rm d}c_2$ can be simultaneously cancelled out; thus, we obtain the expression for${\rm d}r_h$ near the horizon, as$ {\rm d}r_h = \frac{12 \mu n^r r}{-12 M+r \left(12+12 c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2+9c_0 c_1 m_g^2r+64 \pi P r^2\right)}. $

(50) Using the relationships connecting the entropy and volume with the radius (i.e.,

${\rm d}S = 2\pi r_h {\rm d}r_h$ and${\rm d}V = 4/3 \pi r_h^2 {\rm d}r_h$ , respectively), we obtain$ {\rm d}S_h = \frac{24\pi \mu n^r r^2}{-12 M+r \left(12+12 c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2+9c_0 c_1 m_g^2r+64 \pi P r^2\right)}, $

(51) $ {\rm d}V_h = \frac{16\pi \mu n^r r^3}{-12 M+r \left(12+12 c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2+9c_0 c_1 m_g^2r+64 \pi P r^2\right)}. $

(52) From these formulas, we obtain

${\rm d}M = T{\rm d}S_h+ \Phi {\rm d}Q+V{\rm d}P+ A {\rm d}c_1+ B {\rm d}c_2$ , which implies that the first law of thermodynamics is recovered for the case of infalling dust.Here, we discuss the validity of the second law via the entropy variation expressed in Eq. (52). For an extremal black hole in which

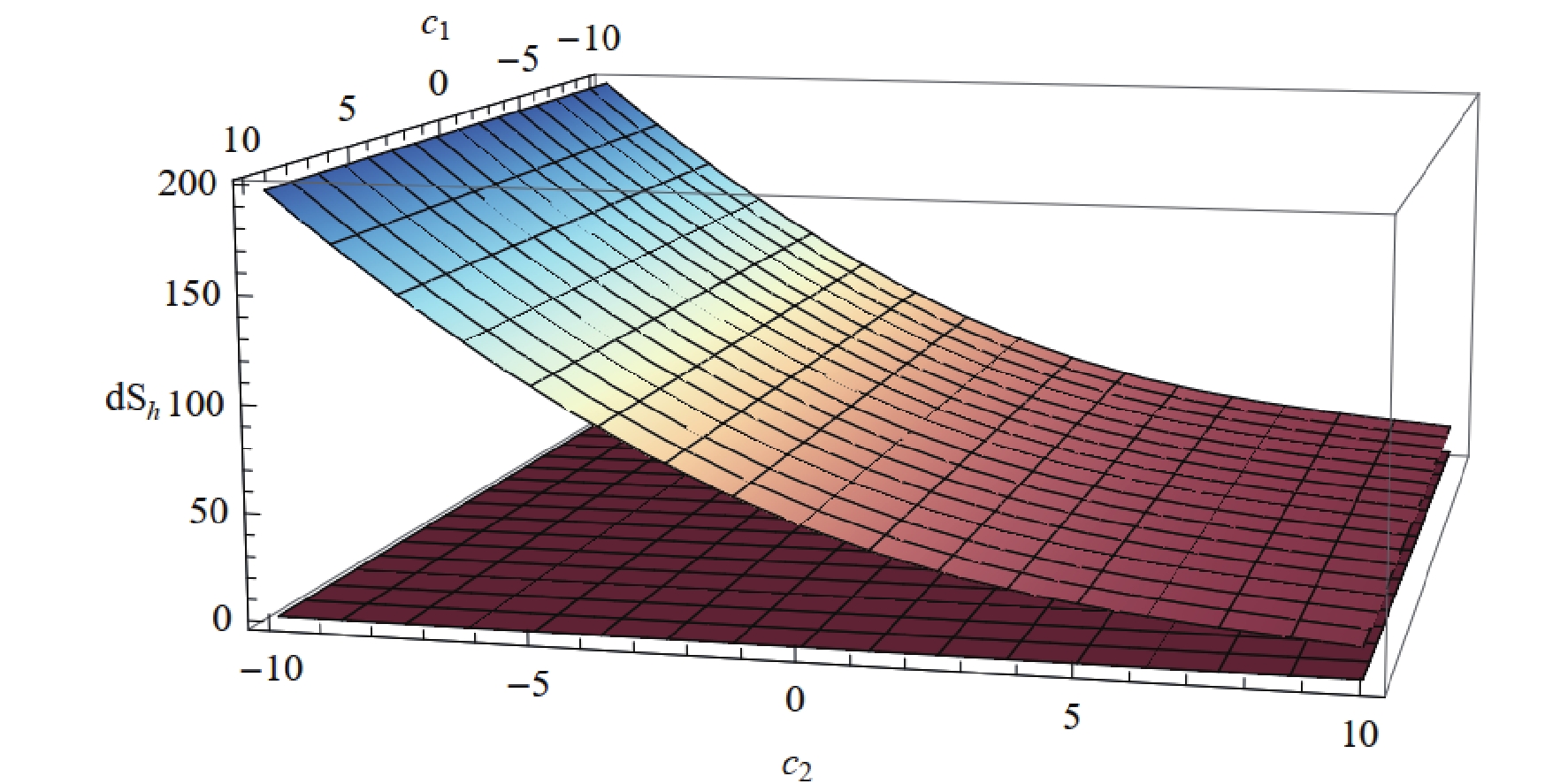

$ T = 0 $ , by substituting Eq. (25) into (52), we can deduce that${\rm d}S_h = \infty$ . For a non-extremal black hole, the event horizon should exceed$ r_h $ . We plot the denominator of${\rm d}S_h$ for the fixed parameters$ c_1 = 5,c_0 = 100, m_g = 0.01, p = 1,M = 2, Q = 0.5 $ for different values of$ c_2 $ ; from this, we conclude that the denominator of${\rm d}S_h$ always exceeds zero, as shown in Fig. 5.From Fig. 6, we can see that

${\rm d}S_h$ remains positive, regardless of the values of$ c_1 $ and$ c_2 $ ; thus, the entropy of the black hole will not decrease. This demonstrates that the second law of thermodynamics is also valid.

Figure 6. (color online) The dependence of

${\rm d}S_h$ on$ c_1 $ and$ c_2 $ after infall of dust.From the above discussion, we concluded that for infalling dust (considered in the extended phase space), the second law of thermodynamics is always valid. This conclusion significantly differs from that of Section 3, where we treated the black hole mass as an enthalpy that is related to the internal energy via

$ U = M-PV-A c_1-Bc_2 $ ; there, the entropy variations were determined by the value of$ c_1 $ and$ c_2 $ . This indicates that the results differ considerably between the two methods. However, in the normal phase space, the conclusions are very similar because the variation of energy in both cases relates to the black hole's mass without the$ PV $ term. For simplicity, we omit the detailed calculations here. -

In this section, we briefly discuss the WCCC under charged particle absorption. The WCCC states that no naked singularity can be seen by an observer at the future null infinity. This means that the singularity should be hidden by the event horizon of the black hole. We consider the variation that occurs as a charged particle is absorbed by a massive black hole, to ensure that the event horizon exists and that the black hole is not destroyed. We primarily follow the strategy used in [33].

There always exists a minimum value of the function

$ f(r) $ for radius$ r_m $ . If the event horizon exists, the condition$ f(r_m)\leqslant 0 $ should be satisfied. At$ r_m $ , we have$ \begin{split} f|_{r = r_m}\equiv f_m = \delta \leqslant 0,\;\; \partial_{r}f|_{r = r_m}\equiv f_m' = 0, \;\; (\partial_{r})^2f|_{r = r_m}\equiv f_m''>0.\end{split} $

(53) For extremal conditions,

$ \delta = 0 $ should satisfied; otherwise,$ \delta $ is a small quantity. After the charged particle has been absorbed by the black hole, the minimum point becomes$r_m+{\rm d}r_m$ . Correspondingly, the variation of$ f(r) $ at$ r = r_m $ is$ \partial_r f|_{r = r_m+{\rm d}r_m} = f_m'+{\rm d}f_m' = 0. $

(54) In the extended thermodynamical phase space, we have

$\begin{split} {\rm d}f_m' =& \frac{\partial{f_m'}}{\partial M}{\rm d}M+\frac{\partial{f_m'}}{\partial Q}{\rm d}Q+\frac{\partial{f_m'}}{\partial P}{\rm d}P\\&+\frac{\partial{f_m'}}{\partial r_m}{\rm d}r_m+\frac{\partial{f_m'}}{\partial c_1}{\rm d}c_1+\frac{\partial{f_m'}}{\partial c_2}{\rm d}c_2 = 0. \end{split}$

(55) The physical parameters of the black hole vary from the initial state

$ (M,Q,P,c_1,c_2,r_m) $ to the final state$(M+{\rm d}M,Q+{\rm d}Q,P+{\rm d}P, c_1+{\rm d}c_1,c_2+{\rm d}c_2,$ $r_m+{\rm d}r_m)$ ; this final state can be expressed as$ \begin{split} f(r_m+{\rm d}r_m) =& f_m+{\rm d}f_m = \delta+\frac{\partial{f_m}}{\partial M}{\rm d}M+\frac{\partial{f_m}}{\partial Q}{\rm d}Q\\&+\frac{\partial{f_m}}{\partial P}{\rm d}P+\frac{\partial{f_m}}{\partial c_1}{\rm d}c_1+\frac{\partial{f_m}}{\partial c_2}{\rm d}c_2, \end{split}$

(56) where

$ \begin{split} \frac{\partial{f_m}}{\partial M}\Big|_{r = r_m} = -\frac{2}{r_m},\; \; \; \frac{\partial{f_m}}{\partial Q}\Big|_{r = r_m} = \frac{2Q}{r_m^2},\; \; \; \frac{\partial{f_m}}{\partial P}\Big|_{r = r_m} = \frac{8\pi r_m^2}{3}, \end{split}$

$ \begin{split} \frac{\partial{f_m}}{\partial c_1}\Big|_{r = r_m} = \frac{c_0 m_g^2r_m}{2},\; \; \; \frac{\partial{f_m}}{\partial c_2}\Big|_{r = r_m} = c_0^2m_g^2. \end{split}$

(57) The crucial information is contained in the sign of Eq. (56). First, we discuss the case for the extremal black hole, where we have

$ \delta = 0 $ . We deform${\rm d}M$ using the condition$ f_m' = 0 $ ; thus,$\begin{split} {\rm d}M =& \frac{\partial{M}}{\partial P}{\rm d}P+\frac{\partial{M}}{\partial Q}{\rm d}Q+\frac{\partial{M}}{\partial c_1}{\rm d}c_1\\&+\frac{\partial{M}}{\partial c_2}{\rm d}c_2+\frac{\partial{M}}{\partial r_m}{\rm d}r_m. \end{split}$

(58) By combining Eq. (58) with (32),

${\rm d}r_m$ can be written as$ {\rm d}r_m = -\frac{r(-2Q {\rm d}Q +2c_1 r {\rm d}A+2 r c_2 {\rm d}B+2 r |P^r|+c_0^2 m_g^2 r^2 {\rm d}c_2+c_0 m_g^2 r^3 {\rm d}c _1+8\pi r^4 {\rm d}P)}{2 Q^2+c_0 c_1 m_g^2 r^3+24 P\pi r^4}. $

(59) Then, inserting Eq. (58) into (55), we deduce that

${\rm d}r_m = 0$ . Applying Eq. (59), we have that$ {\rm d}P = \frac{2Q {\rm d}Q -r(2c_1 {\rm d}A+2c_2 {\rm d}B+2 |P^r|+c_0^2 m_g^2 r {\rm d}c_2+c_0 m_g^2 r^2 {\rm d}c _1)}{8 P\pi r^4}. $

(60) Substituting Eqs. (60) and (59) into (56), the transformation

$f(r_m+{\rm d}r_m)$ can be expressed as$ f_m+{\rm d}f_m = -\frac{2 |P^r|}{r_m}. $

(61) The negative value following the absorption of a charged particle implies that the final state of the extremal black hole is a non-extremal black hole. This means that the event horizon always exists, which implies that the WCCC is valid in the extended phase space for the extremal black hole.

For the case of a near-extremal black hole, the minimum value of

$ \delta $ is a small quantity, which we label as$ f(M,P,Q,c_1,c_2,r_m) = \delta_\epsilon $ . Besides this, the value of$ f'(r_m) $ is very close to zero. Thus, we use$ r_m = r_0(1-\epsilon) $ to ensure a near-extremal case, because Eq. (32) cannot be used directly; here,$ 0<\epsilon\ll 1 $ . Then, we expand Eq. (32) near the minimum point as$ \begin{split} {\rm d}M =& \frac{Q}{r_m}{\rm d}Q+\frac{c_0^2 m_g^2 r_m}{2} {\rm d}c_2+\frac{c_0 m_g^2 r_m^2}{4} {\rm d}c_1 +\frac {4\pi r_m^3}{3} {\rm d}P\\ &+ \left (\frac12+\frac{c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2 }{2} -\frac{Q^2}{2r_m^2}+\frac{c_0 c_1 m_g^2 r_m}{2} +4p\pi r_m^2 \right){\rm d}r_m \\& + \left(\frac{c_0^2 m_g^2 }{2} {\rm d}c_2+\frac{c_0 c_1 m_g^2}{2} {\rm d}r_m+\frac{Q^2}{r_m^3}{\rm d}r_m-\frac{Q}{r_m^2}{\rm d}Q\right. \end{split} $

$ \begin{split}&\left.+\frac{c_0 m_g^2 r_m}{2} {\rm d}c_1+8 p\pi r_m {\rm d}r_m+4\pi r_m^2 {\rm d}P\right)\epsilon\\& + \left(\frac{c_0 m_g^2}{4} {\rm d}c_1+4 P \pi {\rm d}r_m -\frac{3Q^2}{2r_m^4}{\rm d}r_m+\frac{Q}{r_m^3}{\rm d}Q \right. \\&+4\pi r_m {\rm d}P \Bigg)\epsilon^2+{\cal{O}}(\epsilon)^3. \end{split} $

(62) Inserting Eq. (62) into (56), we obtain

$ \begin{split} {\rm d}f_m =& \left(-\frac{c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2}{r_m}-c_0 c_1 m_g^2-8 \pi P r_m+\frac{Q^2}{r_m^3}-\frac{1}{r_m}\right){\rm d}r_m\\& + \left(-c_0 m_g^2 {\rm d}c_1-\frac{c_0^2 m_g^2}{r_m} {\rm d}c_2+\frac{2 Q}{r_m^3} {\rm d}Q-8 \pi r_m {\rm d}P\right.\\&\left.-\left(\frac{ c_0 c_1 m_g^2}{r_m}+\frac{2 Q^2}{ r_m^4}+16 \pi P \right) {\rm d}r_m\right)\epsilon \\& + \left(-\frac{c_0 m_g^2}{2 r_m}{\rm d}c_1-\frac{2Q}{r_m^4}{\rm d}Q-8 \pi {\rm d}P -\left(\frac{8 \pi P}{r_m}-\frac {3Q^2}{r_m^5}\right){\rm d}r_m\right)\epsilon^2\\&+{\cal{O}}(\epsilon)^3. \end{split} $

(63) We solve the expression for

$ P $ using$ f'(r_m) = 0 $ , obtaining$ P = \frac{Q^2-r_m^2-c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2 r_m^2 -c_0 c_1 m_g^2 r_m^3}{8\pi r_m^4}. $

(64) Thus, the expression of

${\rm d}P$ reads$ \begin{split} {\rm d}P =& \frac{Q}{4\pi r_m^4}{\rm d}Q-\frac{c_0^2 m_g^2 }{8\pi r_m^2}{\rm d}c_2-\frac{c_0 m_g^2}{8\pi r_m}{\rm d}c_1\\& + \left(\frac{-2r_m-2c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2 r_m-3 c_0 c_1 m_g^2 r_m^2}{8\pi r_m^4} \right.\\&\left.-\frac{Q^2-r_m^2-c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2 r_m^2-c_0 c_1 m_g^2 r_m^3}{2\pi r_m^5}\right){\rm d}r_m. \end{split} $

(65) Substituting Eqs. (64) and (65) into (63), we obtain

$\begin{split} {\rm d}f_m =& \left(\frac{c_0 m_g^2}{2 r_m}{\rm d}c_1+\frac{c_0^2 m_g^2}{ r_m^2}{\rm d}c_2-\frac{4Q}{r_m^4}{\rm d}Q+\left(\frac{6Q}{r_m^5}-\frac{1}{r_m^3}\right.\right.\\&\left.\left.-\frac{c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2}{r_m^3}\right){\rm d}r_m \right)\epsilon^2+ {\cal{O}}(\epsilon)^3, \end{split}$

(66) such that

$ \begin{split} f_m+{\rm d}f_m =& \delta_\epsilon+\left(\frac{c_0 m_g^2}{2 r_m}{\rm d}c_1+\frac{c_0^2 m_g^2}{ r_m^2}{\rm d}c_2-\frac{4Q}{r_m^4}{\rm d}Q\right.\\&\left.+\left(\frac{6Q}{r_m^5}-\frac{1}{r_m^3}-\frac{c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2}{r_m^3}\right){\rm d}r_m \right)\epsilon^2+{\cal{O}}(\epsilon)^3 \\ =& -\left(8P\pi+\frac{Q^2}{r_m^4}+\frac{c_0c_1m_g^2}{2r_m}\right)\epsilon^2+\left(\frac{c_0 m_g^2}{2 r_m}{\rm d}c_1+\frac{c_0^2 m_g^2}{ r_m^2}{\rm d}c_2\right.\\&\left.-\frac{4Q}{r_m^4}{\rm d}Q+\left(\frac{6Q}{r_m^5}-\frac{1}{r_m^3}-\frac{c_0^2 c_2 m_g^2}{r_m^3}\right){\rm d}r_m \right)\epsilon^2+{\cal{O}}(\epsilon)^3, \end{split} $

(67) where in the second line we have introduced

$ \delta_\epsilon = -(8P\pi+ Q^2/r_m^4+c_0c_1m_g^2/2r_m)\epsilon^2+{\cal{O}}(\epsilon)^3 $ for the near-extremal black hole. Evidently,$ \delta_\epsilon $ is always negative, its leading term is$ \delta_\epsilon\sim\epsilon^2 $ , and the leading order of${\rm d}f_m$ is in the form of${\rm differential\; quantities}\, \times \epsilon^2$ . In Eq. (67), the coefficients expressed as differential quantities in the second term cannot be compared with the negative finite coefficient in the first term; hence, its total value is always negative, which implies that weak cosmic censorship remains valid for near-extremal black holes.Thus, under particle absorption, although the second law of thermodynamics may be violated for certain model parameters, the WCCC remains valid in the extended phase space.

We proceed to verify the WCCC in the normal phase space. To this end, we write the changes in the black hole's conserved quantities as

$(M+{\rm d}M,Q+{\rm d}Q)$ ; thus, the locations of the minimum value and event horizon can be written as$r_m+{\rm d}r_m$ and$r_h+{\rm d}r_h$ , respectively. Subsequently, the variation of$f(r_m+{\rm d}r_m)$ is obtained as$ f(r_m+{\rm d}r_m) = f_m+{\rm d}f_m = \delta+\frac{\partial{f_m}}{\partial M}{\rm d}M+\frac{\partial{f_m}}{\partial Q}{\rm d}Q. $

(68) At

$r_m+{\rm d}r_m$ , the variation of$ f(r) $ is defined as${\rm d}f_m$ ; then, considering$ f'_m = 0 $ , we have$ {\rm d}f'_m = \frac{\partial{f'_m}}{\partial M}{\rm d}M+\frac{\partial{f'_m}}{\partial Q}{\rm d}Q+\frac{\partial{f'_m}}{\partial r_m}{\rm d}r_m . $

(69) Furthermore, using the condition

$ f'_m = 0 $ , we obtain$ M $ and subsequently${\rm d}M$ as$ {\rm d}M = {\rm d}R \left(-\frac{1}{2} c_0 c_1 m_g^2 r-8 \pi P r^2-\frac{Q^2}{r^2}\right)+\frac{2 Q }{r}{\rm d}Q. $

(70) Inserting Eq. (70) into (69), we get

$ {\rm d}R = \frac{2 r (|P^r| r-Q{\rm d}Q )}{c_0 c_1 m_g^2 r^3+16 \pi P r^4+2 Q^2}. $

(71) Combining Eqs. (70) and (68), we obtain an expression for the minimum point, as

$ f_m+{\rm d}f_m = -\frac{2 |P^r|}{r}, $

(72) which is identical to the result (Eq. (61)) for the extended phase space. We do not repeat the discussions here.

From the above analysis, we can conclude that under particle absorption, weak cosmic censorship holds in both the extended and normal phase spaces, even though the second law of thermodynamics may be violated for certain model parameters. Thus, the violation of the second law of thermodynamics (under this assumption) does not affect the WCCC. Hence, we argue that the assumption in the first method may be the cause of second law's violation and requires careful further treatment.

-

In this paper, we studied the thermodynamical laws of massive gravity black holes, using two methods. First, we investigated their thermodynamics properties by considering a charged particle being absorbed by a black hole, and we checked the validity of the thermodynamical laws in both the normal and extended phase spaces. Under this method, the first law remained valid, whereas the expression of the entropy could be negative depending on the model parameters; furthermore, the second law of thermodynamics could be violated in an extended thermodynamical phase space in which the cosmological constant is treated as the pressure of the black hole. For the case with normal thermodynamics (i.e., without the

$ PV $ term), this violation does not occur.Then, we applied a second method that considers a shell of dust falling into a massive gravity black hole; here, the mass of the shell could be directly calculated as it approached the black hole horizon. We found that the expressions for the horizon and entropy always exceeded zero, which implies that the first and second laws of thermodynamics are always valid in both cases, with or without the

$ PV $ term. We summarize our results in Table 3.Thermodynamics of black hole Thermodynamic laws Method with charged particle absorbed Method with shell of dust falling Normal First Law Satisfied Satisfied Second Law Satisfied Satisfied Extended First Law Satisfied Satisfied Second Law Entropy could be negative depending on model parameters Satisfied Table 3. Summary of the validity of the first and second laws of thermodynamics in the normal space and extended spaces.

We argued that the violation of the second law in the extended thermodynamical phase space may be a consequence of the assumption in the first method, which states that the particle affects the internal energy of the black hole. Thus, this assumption should be treated carefully.

Finally, we verified the WCCC for the first method. Our analysis showed that weak cosmic censorship is always valid in both the normal and extended phase spaces. This further supports our hypothesis that the aforementioned assumption may contribute to the violation of the second law of thermodynamics.

In [78], it was argued that under this assumption, when the particle energy increases

$ M $ , it simultaneously increases$ V $ ; as a result, the increase in internal energy is less than the increase in enthalpy, and the assumption is not appropriate. Moreover, the second law of thermodynamics is known to play a fundamental role in physics. Thus, its violation in extended black hole thermodynamics deserves careful investigation of several questions; for instance, what are the underlying physics of the violation? Is it natural to treat the cosmological constant as a variable in extended thermodynamics? Further investigations pertaining to these issues are called for.We are thankful to De-Chang Dai,Yen Chin Ong, and Jian-Pin Wu for helpful discussions.

-

In this appendix, we present the technique used for calculating the mass

$ \mu $ of the shell, which is equal to the change in mass${\rm d}M$ of the black hole when the shell of dust infalls near the horizon, as proposed in [79]. Considering$ \tau $ to be the proper time measured by an observer at rest in the dust, and specifying the shell motion as$ r(\tau) $ , the metric of the shell can be expressed as$ {\rm d}s^2 = -{\rm d}\tau^2+R^2(\tau)({\rm d}\theta^2+\sin^2{\theta}{\rm d}\phi^2), \tag{A1}$

(73) where

$ R(\tau) = r(\tau) $ and$ 4\pi R^2 $ denotes the surface area of the shell at$ \tau $ . We consider the continuity equation,$ 0 = \frac{{\rm d}\sigma}{{\rm d}\tau}+\sigma u^i|_i = (\sigma u^i)|_i = (\sigma(^{(3)}g)^{\frac{1}{2}}u^i),_i/(^{(3)}g)^{\frac{1}{2}}, \tag{A2} $

(74) where

$ \sigma $ is the surface mass density and$ ^{(3)}g $ is the determinant of the 3-dimensional metric. Combining this with$ u^\tau = 1 $ and$ ^{(3)}g = R^4(\tau) $ , we obtain that$ (\sigma R^2)_{,\tau} = 0 $ , which implies that the rest mass of the shell is a constant with$ 4\pi R^2 \sigma = \mu $ .The discontinuity in extrinsic curvature

$ K $ is defined as$ [K_{ij}] = 8\pi\sigma(u_i u_j+\frac{1}{2}^{(3)}g_{ij}) $ (see [79] for more details), where$ u $ denotes the 4-velocity. To proceed, we calculate the$ [K_{\theta\theta}] $ component as$ [K_{\theta\theta}] = 8\pi\sigma\left(u_\theta u_\theta+\frac{1}{2}^{(3)}g_{\theta\theta}\right) = 4\pi \sigma^{(3)}g_{\theta\theta} = \mu.\tag{A3} $

(75) On the other hand, the component

$ K_{\theta\theta} $ can be computed from the definition as$ K_{\theta\theta} = -n_{\theta;\theta} = n_\alpha \Gamma_{\theta\theta}^\alpha = -\frac{1}{2}n^rg_{\theta\theta,r} = -r n^r. \tag{A4} $

(76) Then, the discontinuity term can be derived as

$ [K_{\theta\theta}] = \mu = -r(n^{r+}-n^{r-}), \tag{A5} $

(77) where

$ n^{r+} $ and$ n^{r-} $ denote the radial components of the normal evaluated in the exterior and interior geometries, respectively.When the shell falls into the black hole, we can calculate the external components

$ n^{r+} $ in the exterior geometry as well as the internal components$ n^{r-} $ in the interior geometry. More specifically, by employing$ u.n = 0 $ and$ n.n = -u.u = 1 $ , we can evaluate the components of$ u $ and$ n $ . Thus, on the shell's exterior we have$ 1 = f(r)(u^t)^2-(u^r)^2/f(r), \tag{A6}$

(78) $ 0 = n_r u^r + n_t u^t,\tag{A7} $

(79) $ 1 = -f(r)^{-1}(n_t)^2+f(r)(n_r)^2.\tag{A8} $

(80) After eliminating

$ u^t,n_t $ , we obtain$ n_r^+ = \left[\frac{1+(u^r)^2/f(r)}{f(r)}\right]_{s+}^\frac{1}{2}. \tag{A9} $

(81) Moreover, we have

$ r = R(\tau) $ and$u^r = {\rm d}R/{\rm d}\tau\equiv\dot{R}$ on the shell; thus, outside the shell, the contravariant component of$ n $ is$ n^{r+}\equiv g^{rr}n_r^+ = \left(f(r)+\dot{R}^2\right)^\frac{1}{2}\mid_{s+}. \tag{A10} $

(82) With the same method, one can obtain

$ n^{r-} = \left(f(r)+\dot{R}^2\right)^\frac{1}{2}\mid_{s-} $ . Therefore, Eq. (77) can be re-evaluated as$ \mu = -R(n^{r+}-n^{r-}) = -R\left[(f(r)+\dot{R}^2)^\frac{1}{2}\mid_{s+}-(f(r)+\dot{R}^2)^\frac{1}{2}|_{s-}\right], \tag{A11} $

(83) which is treated as the

${\rm d}M$ , the change of the mass when the shell approaches the horizon.

Revisiting black hole thermodynamics in massive gravity: charged particle absorption and infalling shell of dust

- Received Date: 2020-02-07

- Accepted Date: 2020-06-11

- Available Online: 2020-10-01

Abstract: In this study, we apply two methods to consider the variation of massive black holes in both normal and extended thermodynamic phase spaces. The first method considers a charged particle being absorbed by the black hole, whereas the second considers a shell of dust falling into it. With the former method, the first and second laws of thermodynamics are always satisfied in the normal phase space; however, in the extended phase space, the first law is satisfied but the validity of the second law of thermodynamics depends upon the model parameters. With the latter method, both laws are valid. We argue that the former method's violation of the second law of thermodynamics may be attributable to the assumption that the change of internal energy of the black hole is equal to the energy of the particle. Finally, we demonstrate that the event horizon always ensures the validity of weak cosmic censorship in both phase spaces; this means that the violation of the second law of thermodynamics, arising under the aforementioned assumption, does not affect the weak cosmic censorship conjecture. This further supports our argument that the assumption in the first method is responsible for the violation and requires deeper treatment.

Abstract

Abstract HTML

HTML Reference

Reference Related

Related PDF

PDF

DownLoad:

DownLoad: